FIELD GUIDE TO IMPACT INVESTING

FOR AUSTRALIAN CHARITABLE TRUSTS & FOUNDATIONS

3rd Edition (V3.1) | 2023

ABOUT THIS FIELD GUIDE

The Field Guide is presented in 8 parts. Click on the navigation menu icon in the top left hand corner of your browser to expand the sections of this document and help you find what you are looking for.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This Field Guide is the result of the collaborative effort of experts from the field, investors, investees, students, and other passionate people keen to see Australia's impact investing ecosystem grow and thrive.

Special thanks in particular to contributors, interviewees, and the supporters listed below.

2018 Advisory Committee

- Kylie Charlton - Chief Investment Officer, Australian Impact Investments

- Lisa George - Global Head, Macquarie Group Foundation, Macquarie Group

- Michael Lynch - Executive Director, Impact Investing, Social Ventures Australia (now Managing Director Social Infrastructure Investment Partners)

- Sally McCutchan - Executive Director, Impact Investing Australia (now Executive Director, Breakthrough Victoria)

- Belinda Morrissey - Chief Executive Officer, English Family Foundation

- Will Richardson - Managing Partner, Giant Leap & Non-Executive Board Member, Alberts

- David Rickards - Executive, Co-Founder, Social Enterprise Finance Australia

- David Ward - Technical Director, Australian Philanthropic Services

Researchers, writers and editors

- Jessica Mendoza Roth, Social Impact Hub

- Rob Haggett, Social Impact Hub

- Mia Sturrock, Social Impact Hub

- Jen Fong, Social Impact Hub

- Kylie Marks, Social Impact Hub

UNSW student research and writing teams

- Rajarshi Roy; Daniel Brockwell; Joel Nasrallah; Erica Balilo; Fanny Fontaine (Semester 2, 2018)

- Alecia Duong; Christopher Chan; Jasalina Patel; Margaret Kesaris; Marit Olstad; Mark Lin; Simone Chaikin (Semester 1, 2018)

- James Li; Naoko Lambert; Celine Tia; Christopher Joannes; Raghav Iyer (Summer 2017-2018)

Updates for Version 3.1:

- Inclusion of latest data from the Global Impact Investing Network GIINSights Reports

- Inclusions of latest data from Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA)

- General formatting updates

WELCOME

This, the Third Edition of the Field Guide to Impact Investing, was created to update and refresh our 2018 Second Edition. The Field Guide provides practical strategies and support for Australian charitable trusts and foundations that use, or are interested in using, impact investing to amplify the impact they can make in their communities and the world more broadly.

The Field Guide includes a step by step guide to help answer the questions:

- What is impact investing?

- How does it compare to traditional investing and how is it different to philanthropy?

- How is impact investing evolving worldwide? And in Australia?

- Why is it important for foundations?

- What are Australian charitable trusts and foundations doing about it?

Parts 1 and 2 provide a general introduction to impact investing, an overview of the global and Australian markets in impact, and explore the range of asset classes, funds, and sectors directed at impact.

Parts 3 to 8 of the Field Guide provide more detailed guidance to Australian charitable trusts and foundations looking to begin, advance or deepen their journeys in impact investing. Challenges and myths that can get in the way of impact investing efforts are explored and debunked, and initiatives and ideas to overcome barriers, both real and perceived, are illustrated.

Case studies from a range of Australian impact investors help to illustrate how impact investing works in practice and provide recent examples of initiatives and experiences from the field. Each story links to extended content - interviews, videos and other material - created to support your journey.

Read on to learn about opportunities, strategies and tactics for advancing your impact investing journey.

PART 1

1.1 Overview of impact investing & its aims

Impact investing… harnesses entrepreneurship, innovation and capital to power social progress… By bringing a third dimension, impact, to the traditional capital market priorities of risk and return, impact investing has the potential to transform our ability to build a better society for all. Social Impact Investment Taskforce (1)

A vibrant impact investing market is growing worldwide, as the private sector and governments seek innovative solutions to address the world’s most pressing challenges. At the same time, investors’ increasing recognition that their investment decisions have an impact on the world and its communities are leading them to seek out opportunities that not only minimise the negative impacts of their investments, but intentionally drive positive impact.

Emerging as a response to the growing challenges facing the world, impact investing has the potential to bring game-changing capital to challenges too large and complex to be addressed or funded by the government, the social sector, or philanthropy alone.

What is impact investing?

The Global Impact Investment Network (GIIN) state that impact investments are investments made into companies, organisations, and funds with the intention to generate measurable social and environmental impact alongside financial return (2).

The 3 key characteristics of impact Investing

When considering what is and what isn't impact investing, it's helpful to understand that there are three core characteristics of an impact investment:

- 1.Intention - the investment opportunity must be designed with a specific objective to achieve social and/or environmental impact. Investments where the impact is unintended are not considered impact investments.

- 2.Measurable impact - the impact is able to be measured and reported.

- 3.Financial return - the return on investment can range from concessionary (below market) through to market-rate and market-beating returns, but there is an expectation of at least return of capital.

Figure 1.0 The core characteristics that define impact investing.

In the past decade, impact investing has developed to provide capital across a range of sectors including sustainable agriculture, conservation, renewable energy, microfinance, and affordable and accessible housing, healthcare and education (3).

Figure 1.1 Adapted from Case Foundation’s A Short Guide to Impact Investing: A primer on how business can drive social change 2015.

The potential for impact investing

Allowing investors to make a meaningful financial return whilst investing in social and/or environmental objectives, impact investing directs the flow of capital towards funding and sustaining the innovative, scalable solutions needed to address the world’s most pressing social and environmental challenges(4). While impact investing is still in an emergent phase, its growth presents excellent opportunities for forward looking investors who know that the only profitable future is a sustainable one.

Figure 1.2 sets out the potential of impact investing for investors, government, not-for-profit organisations (NFPs), social ventures, and the community.

1.2 Financial returns & impact in tandem

The expectation of financial return differentiates impact investing from philanthropy, and the specific objective of making and measuring impact differentiates it from traditional forms of investment.

Figure 1.3 Impact investing in context, financial return and impact.

The terms impact investing, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing and Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) are often used synonymously, but impact investing is distinctly different from ESG and SRI and other forms of ethical or socially responsible investing and it is helpful to understand these differences. Figure 1.4 shows the spectrum of common investment typologies.

ESG and SRI generally apply a set of negative or positive screens to an investment. Negative screening involves avoiding or excluding investments with low environmental, social or governance metrics, and screening companies under certain criteria. In contrast, impact investing goes beyond passive screening by seeking investment opportunities with the goal of affecting either or both social and environmental change with returns that may be below, at, or above market.

As Figure 1.4 shows, across the spectrum of impact investments, there are varying levels of financial return, reflecting the differing risk appetites and requirements for financial return from various investors. (5) Adapted from Impact Investment Spectrum by Sonen Capital. (6)

Impact-first, finance-first, or blended value?

The following terms are sometimes used to describe approaches to impact investment with respect to financial and social/environmental return.

Finance-first Impact Investments seek to maximise financial return while aiming to make a real and measurable impact. This means that investors set minimum impact objectives that must be considered when selecting investments, however the expectation is that these investments will generally achieve financial returns that are competitive with traditional investments.

Impact-first Impact Investments seek to maximise social and/or environmental impact while still making a financial return. The financial return may be above or below risk-adjusted market rates of return. Impact-first investors are primarily driven by their desire to create impact and are therefore willing to accept a below market financial return and/or take higher risks to achieve these objectives. Philanthropic trusts and foundations are more likely to use this type of investment as an adjunct to their granting strategy, rather than institutional investors.

While impact-first and finance-first distinctions may be helpful in characterising opportunities and investment styles for some, there is a growing trend towards investors managing for total performance. (7)

‘Both/and’ or Blended Value Investments seek to create sustainable, long-term solutions to global challenges through strategies that neither prioritise economic return nor social return, but rather a blend of both. They are located in a space between philanthropy, where no financial return is expected, and pure financial investments, which does not focus on social or environmental outcomes.

While some investors believe impact investments will lead to smaller returns, with a trade-off between financial return and social impact, history has shown this is generally not the case.

There’s a persistent myth that impact investing automatically necessitates a trade-off in financial performance… But it’s quite feasible for impact investors to make competitive returns.” Abhilash Mudaliar, Paul Ramsay Foundation (8)

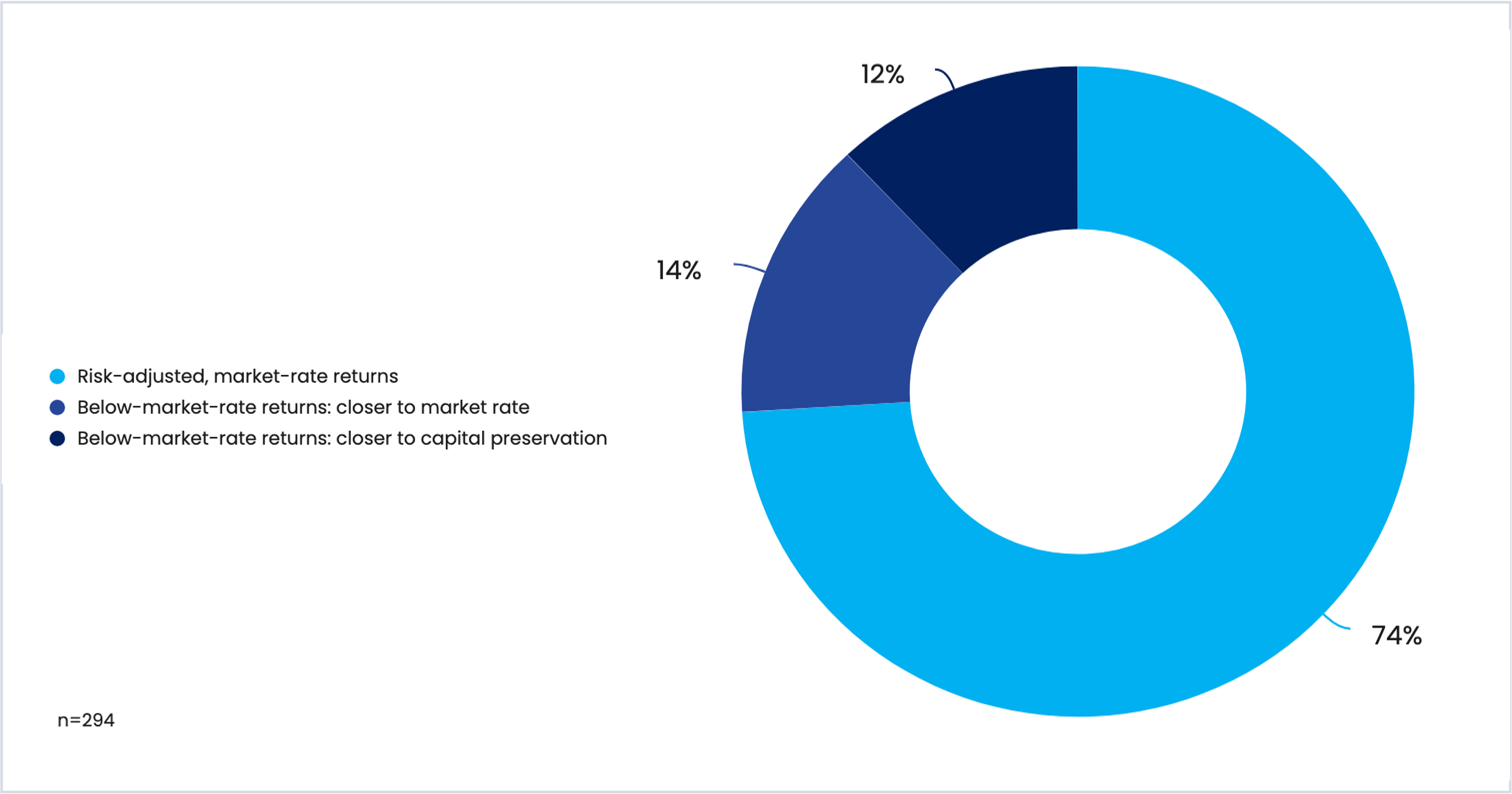

While impact investors target financial returns along a spectrum ranging from capital preservation to market-rate, it should be noted that most respondents in the GIIN's '2023 GIINsight: Impact Investor Demographics' report continue to target risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, with this increasing from the 2020 report:

Figure 1.5 Adapted from Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), 2023 GIINsight: Impact Investor Demographics (29)

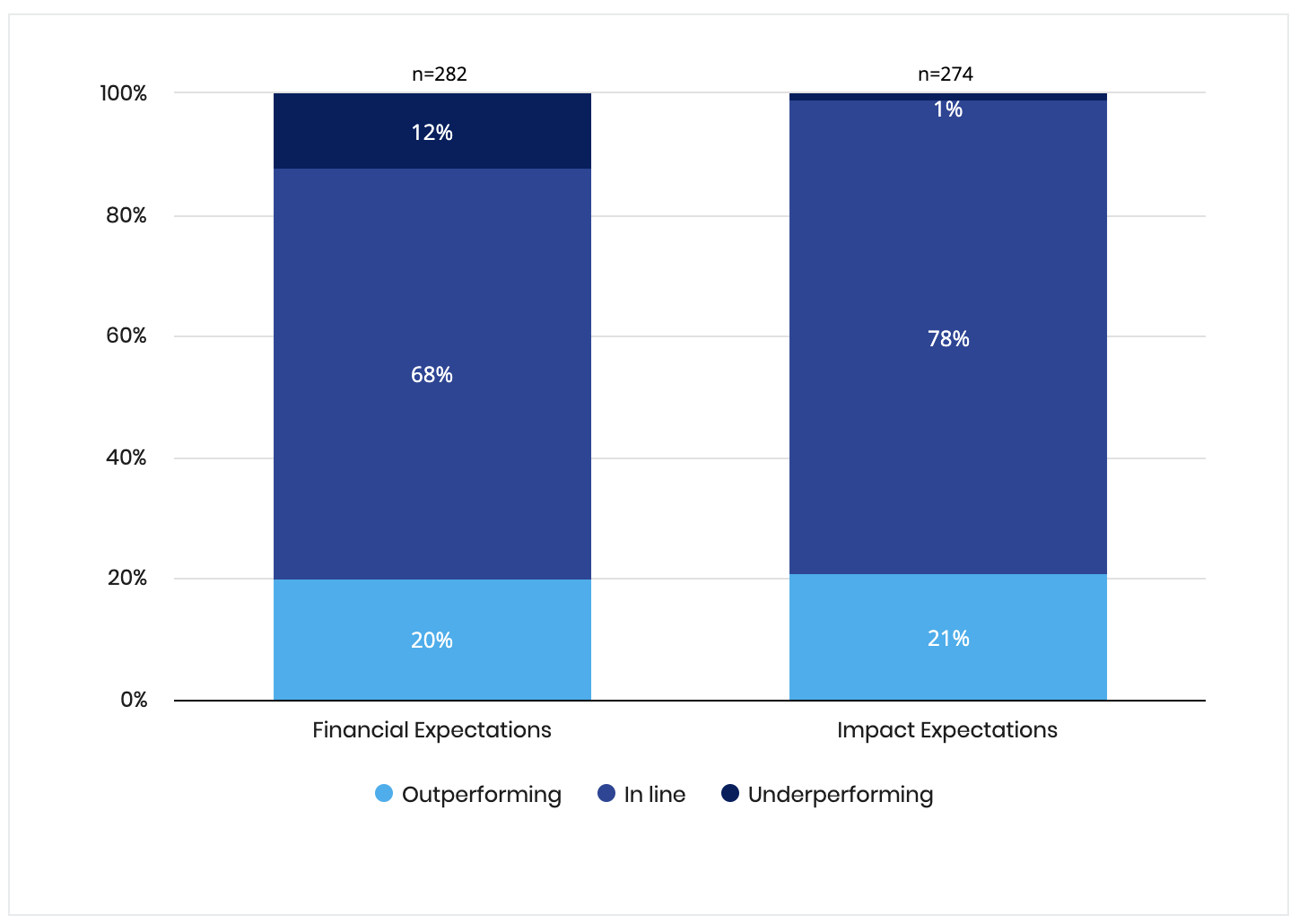

The GIIN’s 2020 survey also revealed that 'an overwhelming majority of respondents reported meeting or exceeding both their impact expectations and their financial expectations (99% and 88%, respectively (10):

Figure 1.6 Performance relative to expectations (Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), 2023 GIINsight: Impact Investing Allocations, Activity & Performance) Note: Excludes two organisations that did not share financial performance relative to expectations and one organisation that did not disclose impact performance relative to expectations. (30)

The GIIN’s conclusion was that impact investors can achieve market rate returns, as general funds for impact investment can perform at similar levels to traditional investment. (10) Paul Ramsay Foundation's Chief Impact Officer, Abhilash Mudaliar, does indicate, however, that below market capital plays a critical role in the industry and will continue to do so. One role the submarket plays is as a bridge between philanthropy and investing. This is explored further in Parts 2 and 8.

1.3 The global impact investing landscape

Just over a decade since a coalition of philanthropists and investors introduced the financial-services industry to the term ‘impact investing’, interest and participation in impact investing has accelerated globally.

The majority of impact investment capital originates from America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region but demand for impact investment extends worldwide. This includes investments made throughout the world into for-profit, hybrid and non-profit ventures spanning a broad range of social and environmental objectives. (11)

Figure 1.7 Organisational representation and impact AUM by headquarters location. Source: GIINsight: Sizing the Impact Investing Market 2022 (12)

It is difficult to accurately determine the current size and potential of the global market due to the broad range of definitions and approaches to impact investment, and estimates vary significantly from organisation to organisation. A current market snapshot from the GIIN's Sizing the Impact Investing Market 2022 report, estimates that the global impact investment market is in excess of $USD 1 trillion (12).

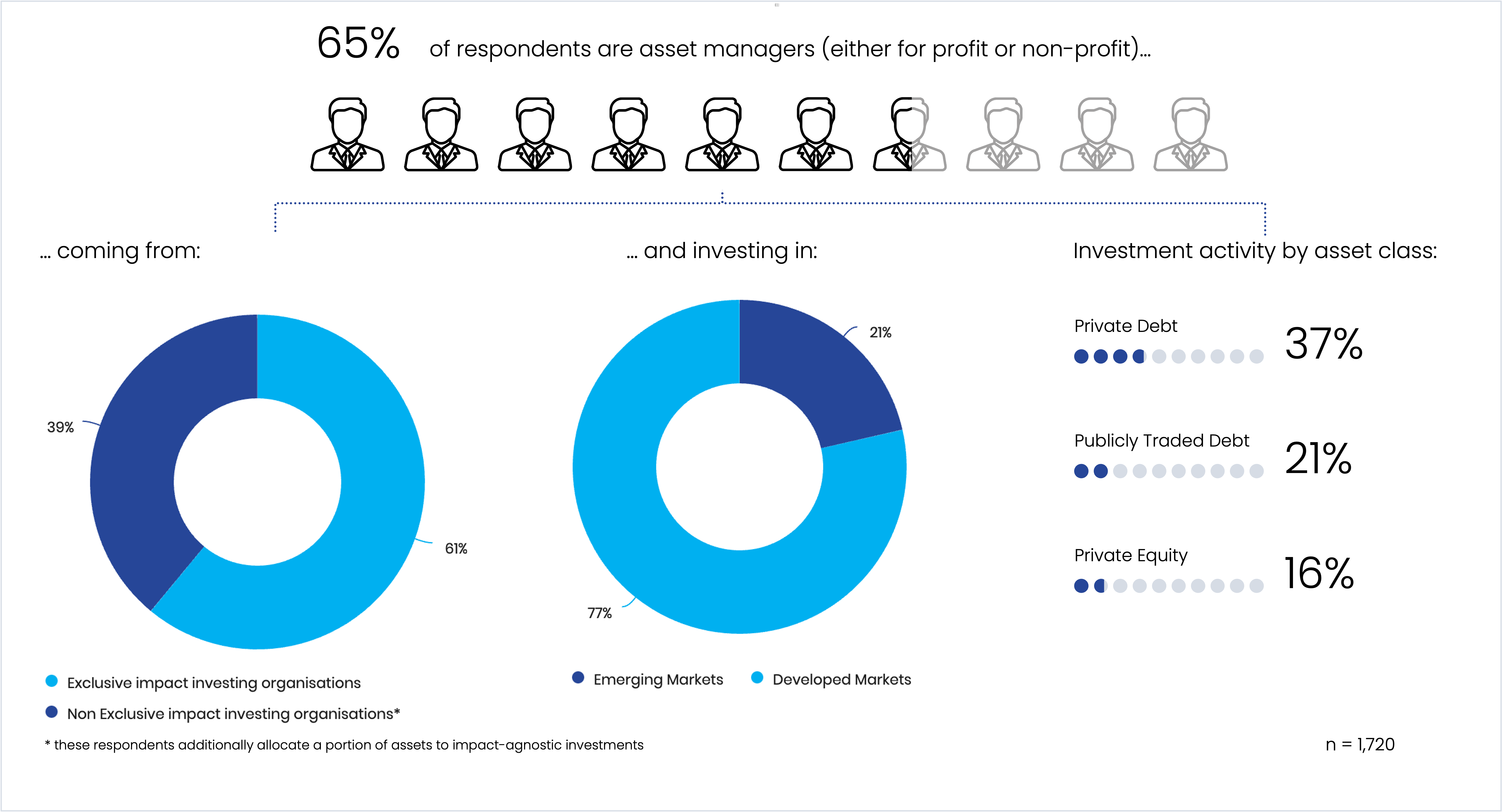

In terms of market trends, Impact Alpha have described a shift of capital into a broader set of 'sustainable' and 'responsible' assets (see Figure 1.4 above for details) (13). The GIIN's research shows that the impact investments are still predominately made by exclusive impact investing organisations (61%) with debt (private and publicly traded) being the main asset allocation (10):

Figure 1.8 Adapted from the GIIN's Annual Impact Investor Survey 2020 (10)

Moving towards the mainstream

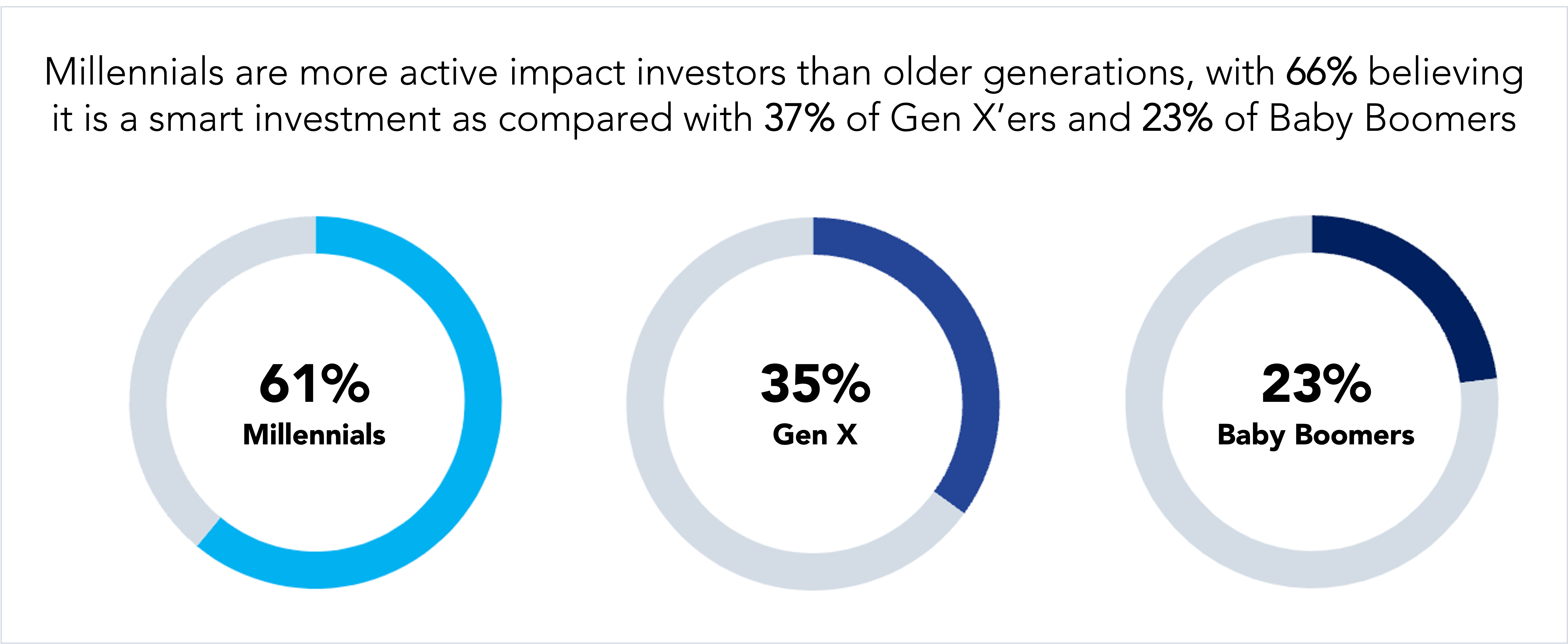

The growth of impact investing globally has been catalysed by policy developments in many countries, the emergence of pioneering market builders, and a growing investment appetite worldwide. Millennials and female investors are increasingly looking to make their asset wealth for impact and are also a driving force behind this investment momentum (14).

Studies by Morgan Stanley’s Institute for Sustainable Investing have found that 18 to 34-year-olds are twice as likely to invest in a portfolio or individual companies if they seek positive environmental or social impact (15). Furthermore, Fidelity Charitable’s 2022 survey found that of the 1,200 investors surveyed, 60% of millennials are involved in impact investing, compared with 34% of all investors. In addition to alignment of values and personal fulfilment, millennials believed that impact investing has greater potential than traditional forms of philanthropy to create long-term positive change (16):

Figure 1.9 Adapted from Fidelity Charitable 'Insights into impact investing Report, 2022 (16)

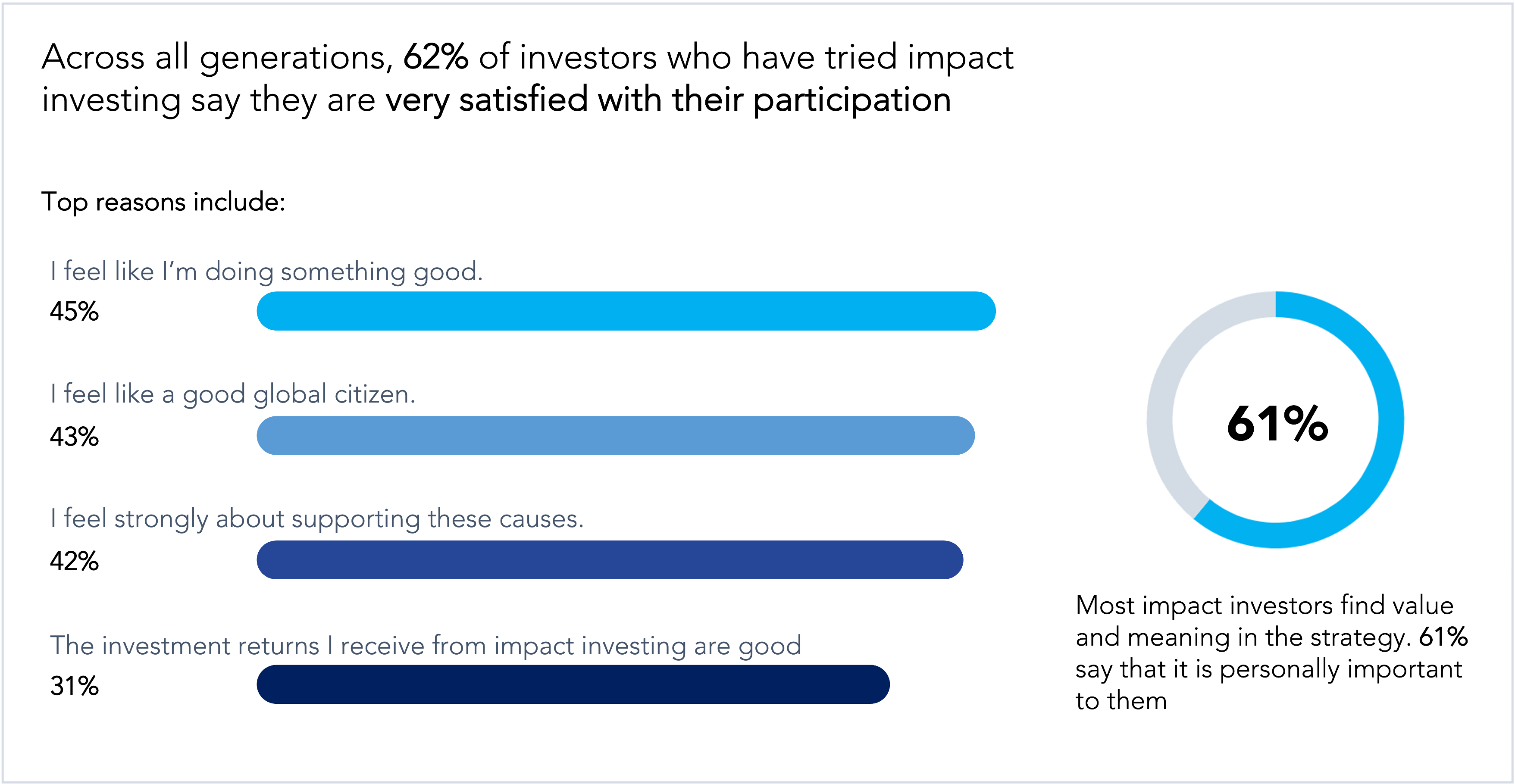

Millennials aside, there is also growing interest in impact investing among high-net worth Gen X (aged 35-51) and those with at least $10 million in investable assets. (17). Fidelity Charitable found this is due to the fact that the majority of impact investors are satisfied with participating in these investments:

Figure 1.10 Adapted from Fidelity Charitable 'Insights into impact investing Report, 2022 (16)

In response to the growing interest and appeal of impact investing, mainstream market investment managers like Bain Capital, BlackRock, Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, and JPMorgan Chase are examples of institutions that have added impact products to their portfolios. (18)

These institutional players typically use an array of benchmarks for ‘impact’. As such, there is a growing need for a common language and shared fundamentals around how the social/environmental value created by impact investments is measured. While this common language is emerging, at present there are still many approaches to managing and measuring impact. As such, Impact investors need to be able to navigate the landscape, consider the impact they are seeking, how they will effectively measure this and how the investment aligns with their portfolio and risk/return considerations. See Part 7: Managing & Measuring Impact for more details on this topic.

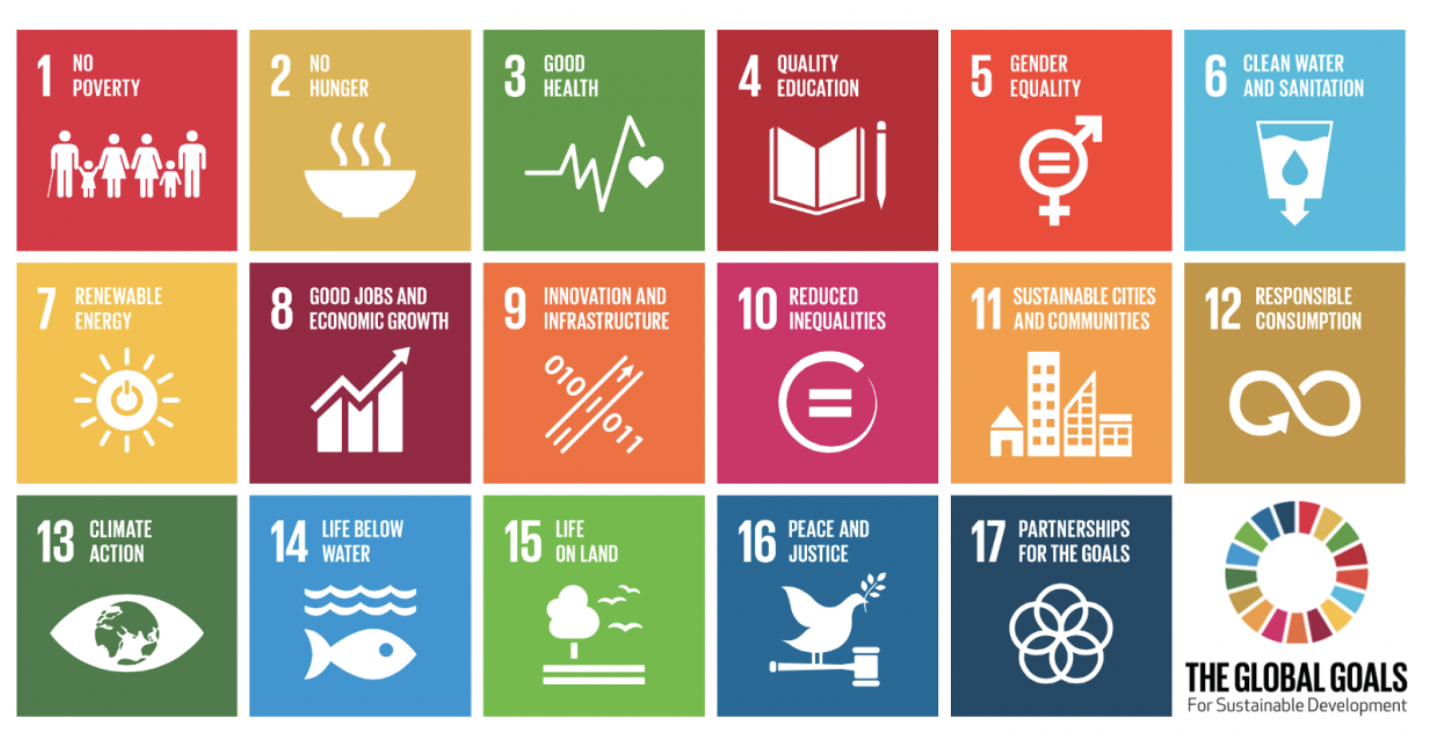

The UN's SDGs and impact investing

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), launched in 2015, provide a global agenda to end poverty and protect the planet by 2030. Each of the 17 goals, shown in Figure 1.11 below, has targets that require financial investment. The UN estimates that funding initiatives to achieve the SDGs will require an additional USD 5–7 trillion per year, and it has emphasised the critical need for collaboration of the private, public, and philanthropic sectors to resource the initiatives needed to achieve the goals to end poverty and ensure environmental sustainability by 2030.

Impact investing will play a pivotal role in unlocking private capital to achieve the goals.

Figure 1.11 The United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs provide an unprecedented and convenient framework with which to structure and modify portfolios to define the impact they aim to make. Investors have been encouraged to consider how their investments might contribute to achieving the goals and some of the largest pension funds, asset managers, and increasingly charitable trusts and foundations are taking up this challenge and are aligning their strategies with the SDGs.

Dutch pension fund PGGM, for example, identified six SDG focal goals in which to invest and, more locally, QBE are mapping their portfolios to the SDGs at a higher level. Importantly, often investments cross multiple goals (for example, a water waste management project involving wetlands development could promote clean water and sanitation, and life on land through biodiversity).

Figure 1.12 Adapted from the GIIN's Annual Impact Investor Survey 2020(10)

The GIIN has created profiles on a variety of impact investors to understand their motivations for tracking performance to the SDGs, and to demonstrate how aligning to the SDGs is helping them develop impact strategies and goals, communicate with stakeholders, and attract new capital. (19).

Figure 1.13 Adapted from the GIIN's Annual Impact Investor Survey 2018 (9)

1.4 Australia's impact investing landscape

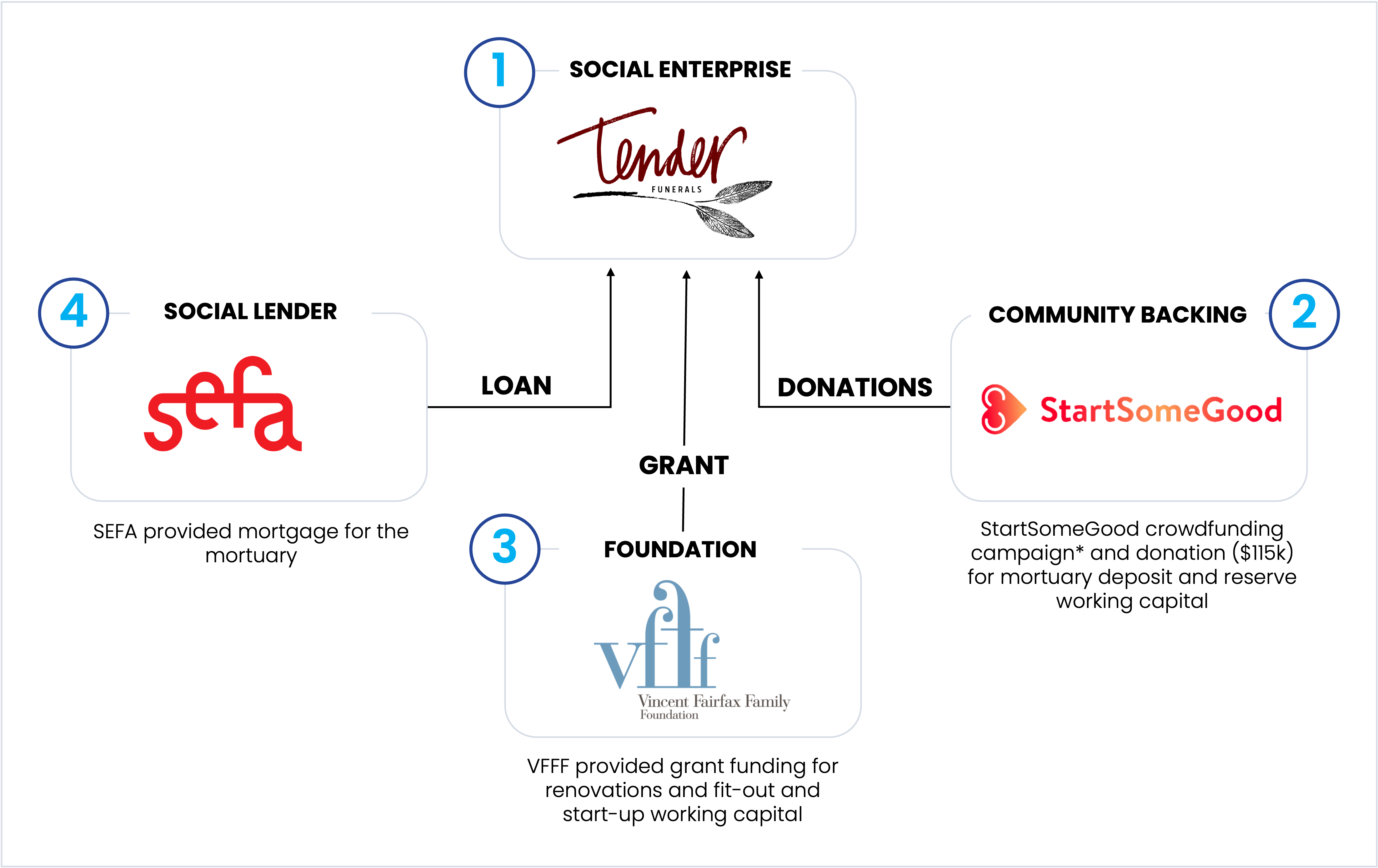

A commercial laundry changing lives one wash at a time. An artisan bakery baking into its business model employment pathways for refugees and asylum seekers. A website empowering people with disabilities to choose their own caregivers. An ecotourism venture using animal attractions to create jobs and conserve precious bushland. A funeral business supporting dignified bereavement through affordable, meaningful and personalised undertaking services. These are all examples of Australian impact investment deals.

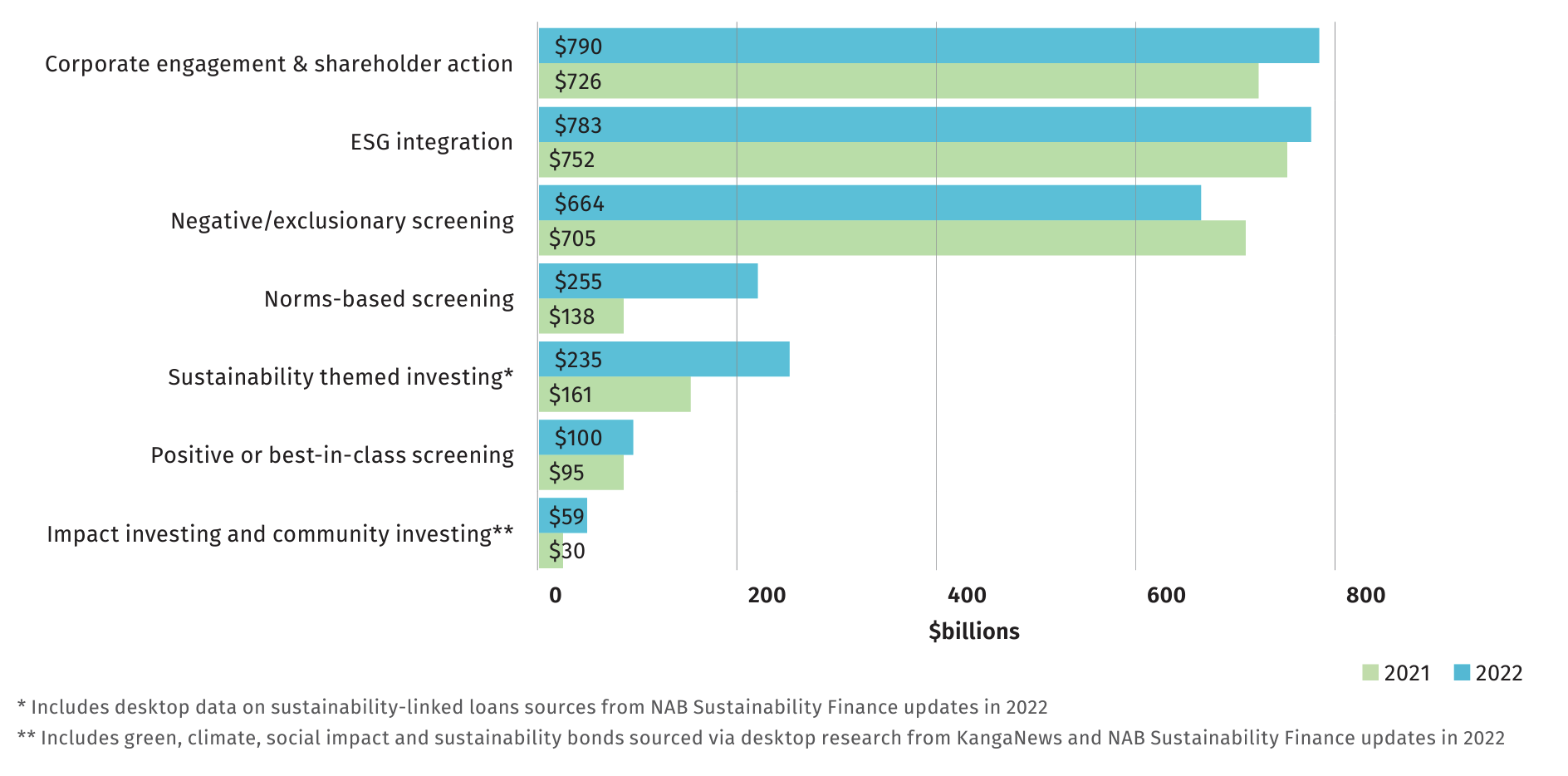

In line with global trends, Australia’s impact investing market has also grown in recent years. RIIA's Responsible Investment Benchmark Report 2023 highlights the growth of the Australian impact investing landscape (31):

- Impact investing is gaining traction in Australia, nearly doubling since 2021 to $59 billion in 2022.

- 38 green, social, impact and climate bonds were issued in 2022, contributing more than $13 billion to a record impact investment figure this year. The majority of bonds are issued by international issuers worth a total of $9.4 billion.

- In 2022, more than 450 homes were financed via impact investment funds, with $18 million allocated to Specialist Disability Accommodation, and more than 450 new tenants were provided with housing.

- Top themes include conservation, environment and agriculture, housing and local amenities and income and financial inclusion.

Despite this growth, it is important to note that in comparison to other responsible investment approaches, impact investing in Australia is still a relatively small market:

Figure 1.14 Where impact investing sits in the total AUM covered by responsible investment approaches of survey respondents, adapted from RIAA's Responsible Investment Benchmark Report 2023 Australia (31)

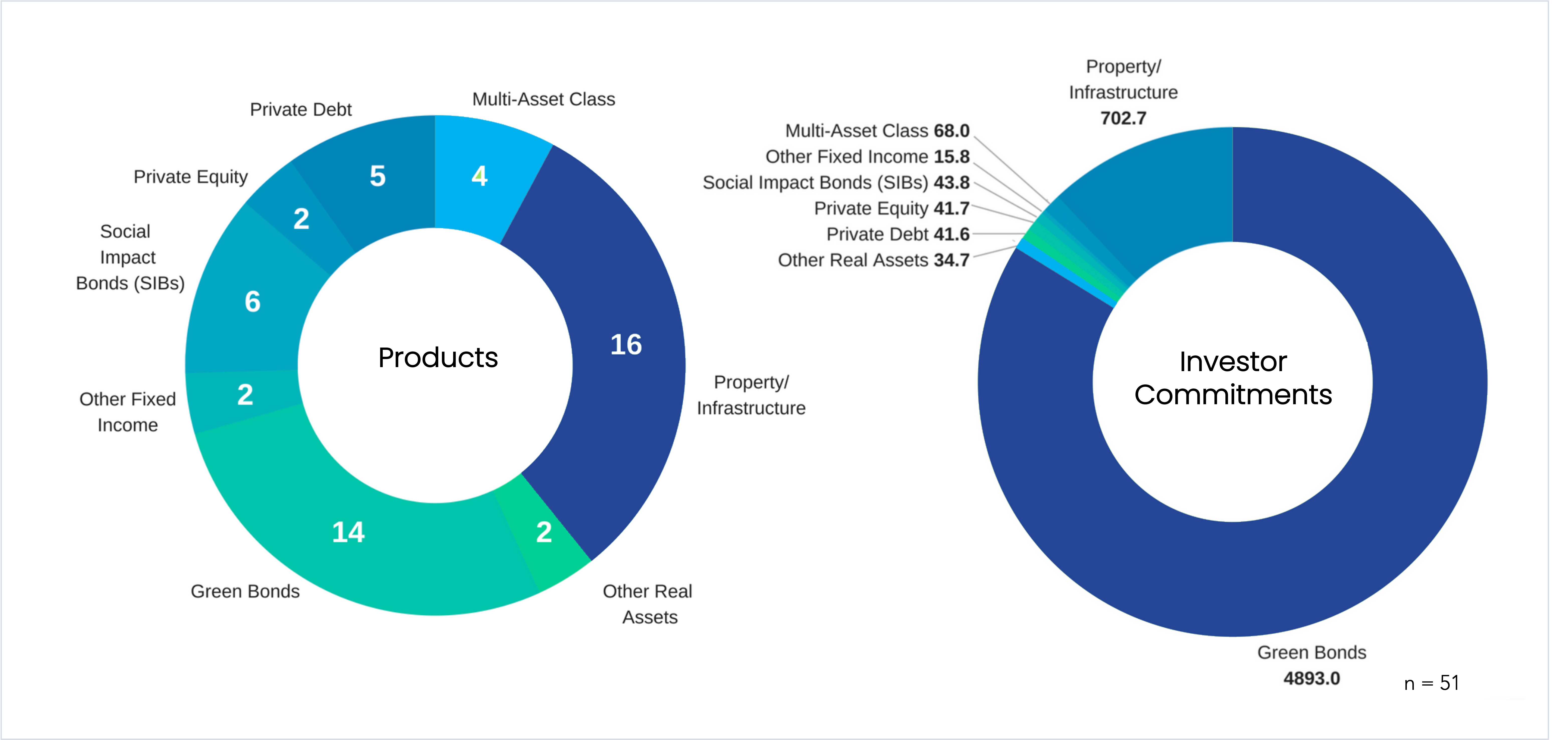

In terms of asset allocations and investor commitments, RIAA have shown that investor commitments are mainly committed to green bonds, across a range of products:

Figure 1.15 adapted from RIAA's Responsible Investment Benchmark Report 2018, the growth of impact investing in Australia. (21)

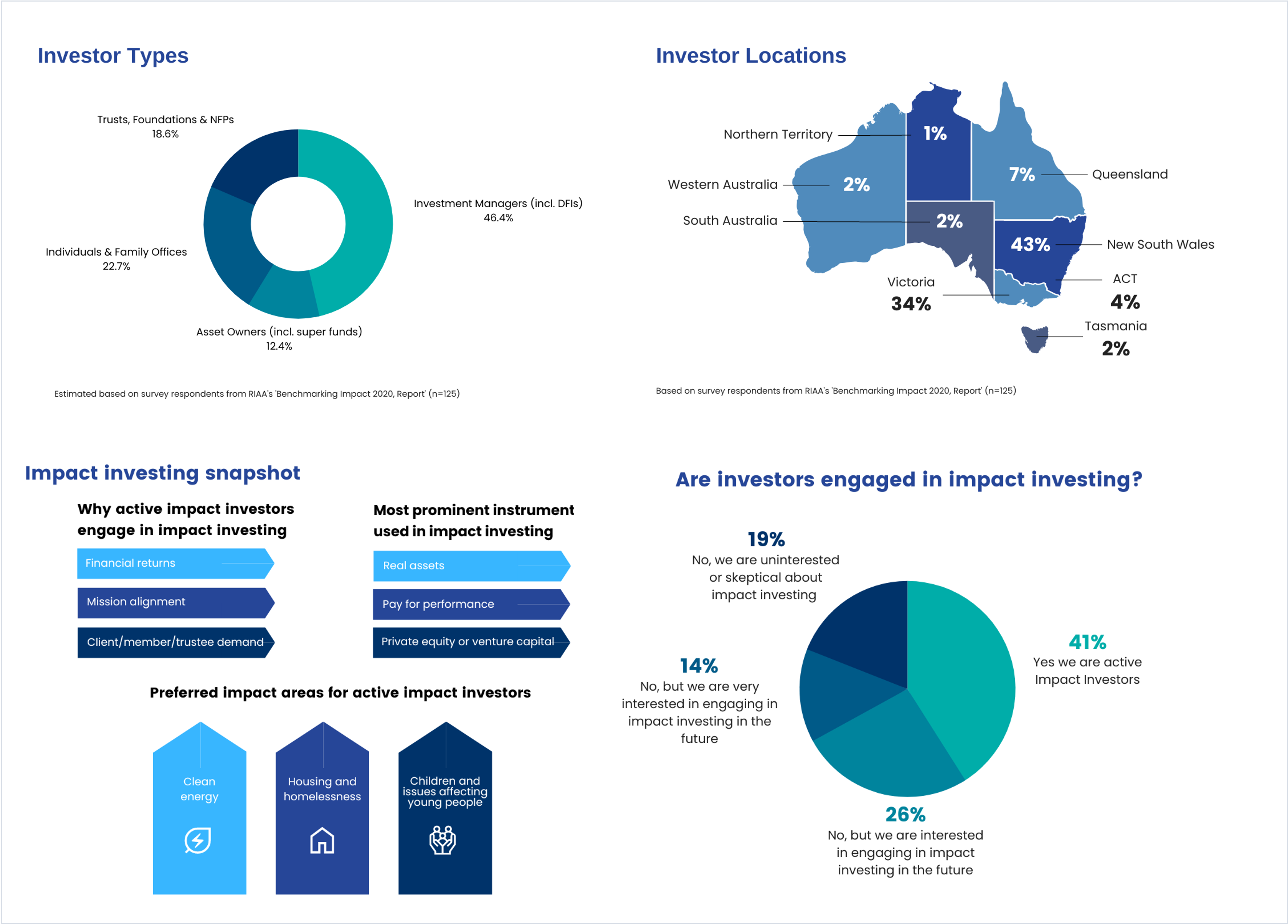

The diagrams below present data extracted from IIA’S 2016 Investor Report, showing where impact investors are located, their motives for impact investing, and their preferred areas for investment.

Figure 1.16 Snapshot of Australian impact investors; who they are; why they impact invest; the instruments they use; and the impact areas in which they prefer to invest. Adapted from IIA's Investor Report and RIAA's Benchmarking Impact 2020 Report.

The Responsible Investment Association Australasia found that 92% of investors’ experience in Australia has largely been in line or exceeded their expectation for market returns (20).

Realising the potential of impact investing in Australia

This is an exciting time for impact investing in Australia. As more players enter the market, and new collaborations result in diverse impact investment opportunities, Australians are set to realise the many benefits of a growing and maturing impact investment market. However, Impact Investing Australia (IIA) indicates that the market is still challenged in areas of scale, availability of data, flow of information and market infrastructure. (22)

The Australian Advisory Board on Impact Investing (AABII) maintains that scaling will require a concerted effort from all key stakeholders, with efforts directed to:

- increasing mainstream awareness of what impact investing is;

- educating investors about opportunities in the space; and

- learning how to design for scale and replicate good ideas. (23)

IIA adds the Australian Government must continue to be actively involved to assist the market in reaching its potential scale by identifying new solutions to issues, and investing to reduce risks for new entrants and enhance investor confidence. (24)

Developments in the space do show that some concerted effort from key players, coupled with government support, is paving the way for stronger growth. For example:

- Government support:

- Since 2017, the Department of Social Services has committed more than $50 million to growing the social impact investing market in Australia and creating innovative solutions to entrenched social issues (25).

- In 2018, as a market capability building initiative, the Federal Government committed $8 million to establish the Social Impact Investment Readiness Fund with the aim of building capacity of for-purpose organisations to be investment ready (26).

- In 2020, The Federal Government also announced a $40 million Emerging Markets Impact Investment Fund (EMIIF) that aims to address the financing gap for small to medium enterprises (SMEs) in the region (27).

- Business support:

- In 2017-18, Indigenous Business Australia injected $50 million into impact funds supporting Indigenous communities. (28)

- In 2018, First State Super (now Aware Super), partnered with the NSW Government to stimulate job creation. The super fund committed $100 million, while the Jobs for NSW unit will invest $50 million into the “GO NSW Equity Fund”. The funds aims were to create up to 2,500 new jobs and a further 2,400 by 2025 using recycled funds.

Other market building initiatives include the launch of the Impact Investing Hub in late 2017. The Impact Investing Hub supports the growth of the Australian impact investment sector by improving access to information about Australian impact investing deals and the market, and by helping to connect investors with investment opportunities.

PART 2

2.1 Overview

The three main areas where impact investments are used are:

- 1.to scale a business or social enterprise;

- 2.to access real assets (eg. property or infrastructure); and

- 3.to finance program delivery. (1)

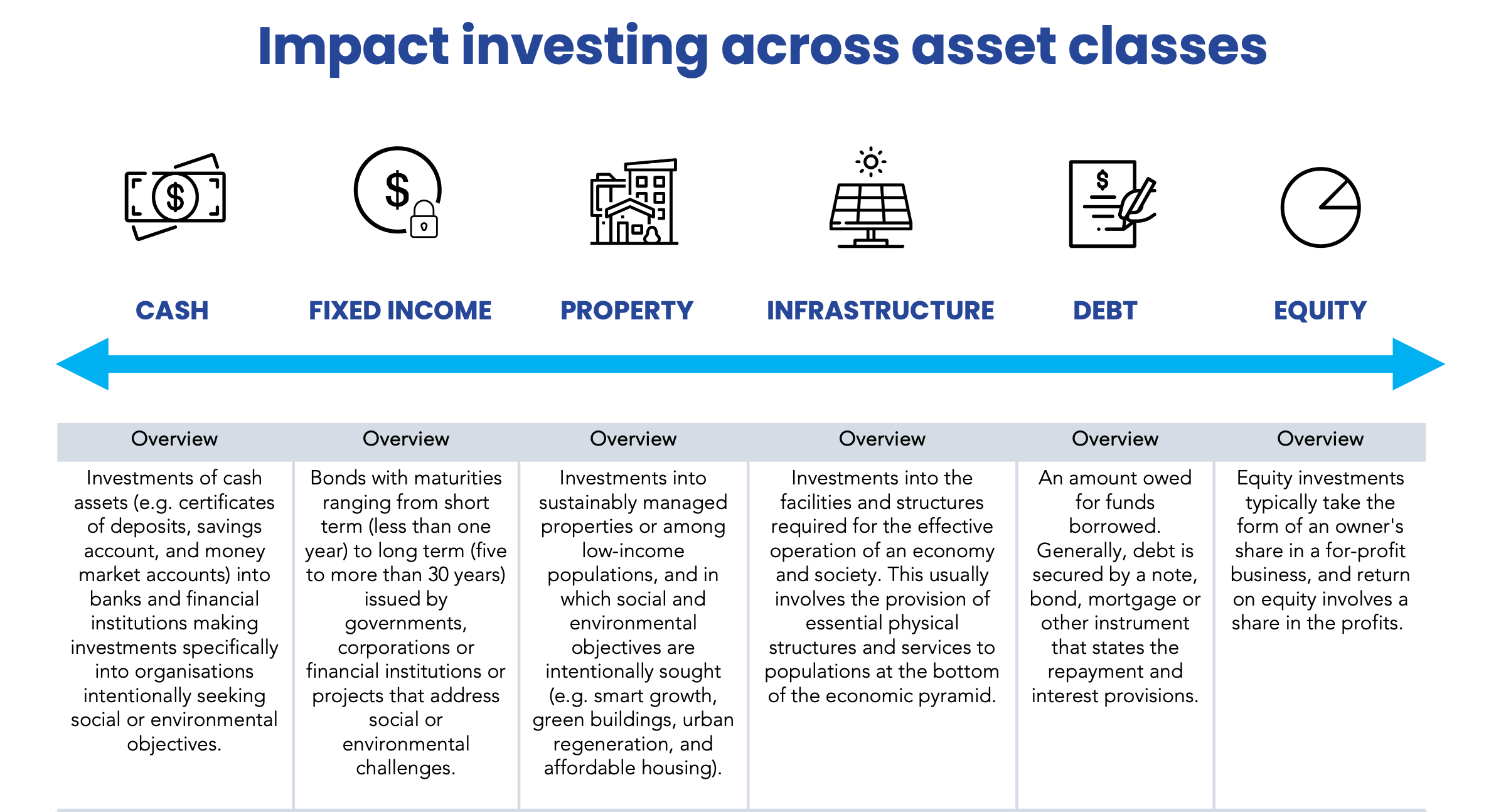

Asset classes and instruments

Impact investing is an investment philosophy that can be applied across a broad range of existing asset classes:

Figure 2.1 adapted from World Economic Forum, An introduction to mainstreaming impact investing initiative, 2013 (2)

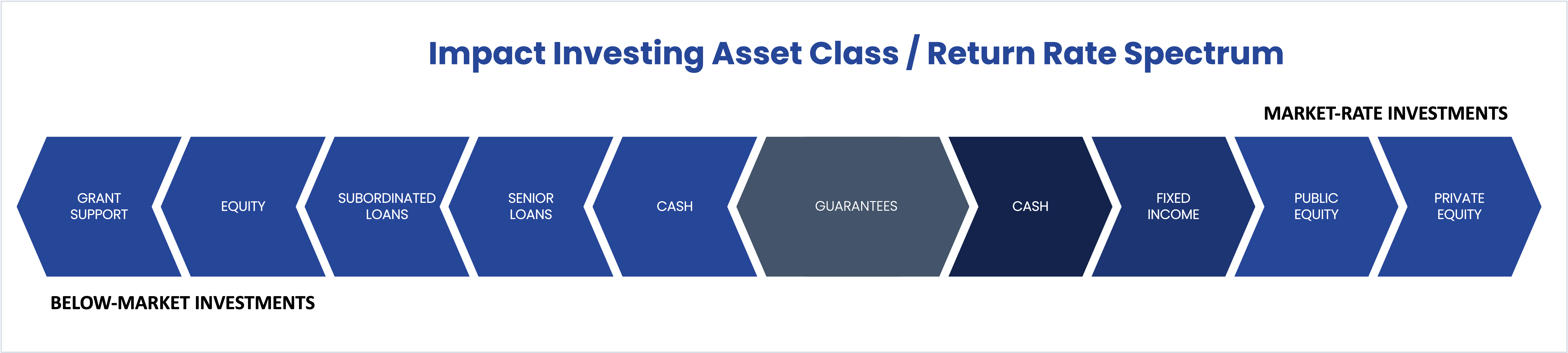

Alongside the asset class, impact investments can be thought of in terms of the target financial returns. These range from below market (sometimes called concessionary) to risk-adjusted market rate, and can be made across asset classes, including but not limited to cash equivalents, fixed income, venture capital, and private equity:

Figure 2.2 adapted from the GIIN classification

In practice, impact investors fund many asset classes using a range of instruments, and blend various types of capital in innovative hybrid funding instruments and structured deals to drive impact across the sector (3).

2.2 Direct investments

Depending on your impact investment strategy, you may have a preference to make direct or indirect investments. A direct investment is when you directly invest in an entity creating impact, while an indirect investment is when you make investments into a fund or another investment vehicle that will invest in entities that create impact.

Explore different examples of impact investment deals in Australia and internationally below:

Equity Investments

Impact focus: Disability services, Employment

Description: Online platform linking support workers and people with disability looking for support, allows people with disability and their families to manage relationships with support workers whose tax and super payments, insurance, payroll and workplace health and safety requirements are taken care of by Hire up.

Structure: $2.4m Equity Raising

Financial Return: Undisclosed

Impact created: Made 8,500+ support connections, provided 600,000+ hours of support and saved $5.3m by Hire up users from their packages to be used for extra hours of support.

Impact focus: Recycling, Environment, Food Wastage

Description: 9.5 million tonnes of food is discarded each year of which 400,000 and 600,000 tonnes are accessible, edible and quality food.

Yume is a revolutionary food rescue platform designed to reduce the amount of commercial food waste heading to landfills each year. Yume is Australia's first surplus food online marketplace where wholesale and retail suppliers and primary producers can post surplus edible and quality food for sale. Yume also facilitates the donation of unsold products to food charities.

Structure: $2.6m Equity Raising

Financial Return: Undisclosed

Impact created: Diverted 176,241kg from landfill and donated 23,209kg to food rescue organisations.

Impact focus: Children, disability

Description: : AbilityMade is an innovative technology company engaged in the customisation and digital manufacture of custom-made orthoses for children with disability. AbilityMade partners with orthotists to leverage advances in 3D scanning and 3D printing to dramatically increase the supply of orthoses.

Structure: $1.0m Equity Raising

Financial Return: Undisclosed

Impact created: Undisclosed

Debt Investments

Impact focus: Mental Health, Employment

Description: Vanguard Laundry Services (VLS) is a social enterprise commercial laundry creating employment opportunities for people previously excluded from the workforce, predominantly due to mental health conditions

Structure: A loan of over $2.1 million. Grants worth $3.2 million and over $770,000 in pro bono assistance

Financial Return: Undisclosed

Impact created: In the first year of operations, Vanguard Laundry Services reduced the number of participants reliant on Centrelink payments from 90.5% to 76.2%, and increased the median fortnightly income of participants by $392. This represented a 38.9% reduction in housing affordability stress.

Impact focus: Employment, Disability services

Description: Jigsaw is a job-focused social enterprise that provides holistic training and employment for people with a disability Structure: $3m capital raise consisting of $2.1 debt investment and $0.9m grant funding

Financial Return: Undisclosed

Impact created: Opened new hubs in Melbourne and Adelaide with plans in place for Canberra and Perth. Further developed Jigsaw Connect, which transitions job ready candidates with disability to open employment

Impact focus: Employment, Disability services

Description: Start-up dedicated to empowering and placing autistic talent into specialised IT roles. Structure: Beneficial Outcomes Linked Debt (BOLD), a $600,000 impact-linked loan scheme, whereby the loan balance decreases when the borrower’s impact increases. More details.

Financial Return: Internal Rate of Return (IRR) expected to be between 5–15%, depending on the level of impact achieved

Impact created: Placement of 60 people in IT jobs

Social Impact Bonds & Payment by Outcomes

Note: Social Impact Bonds & Payment by Outcomes (PBO) are discussed in more detail in the subsequent sections below.

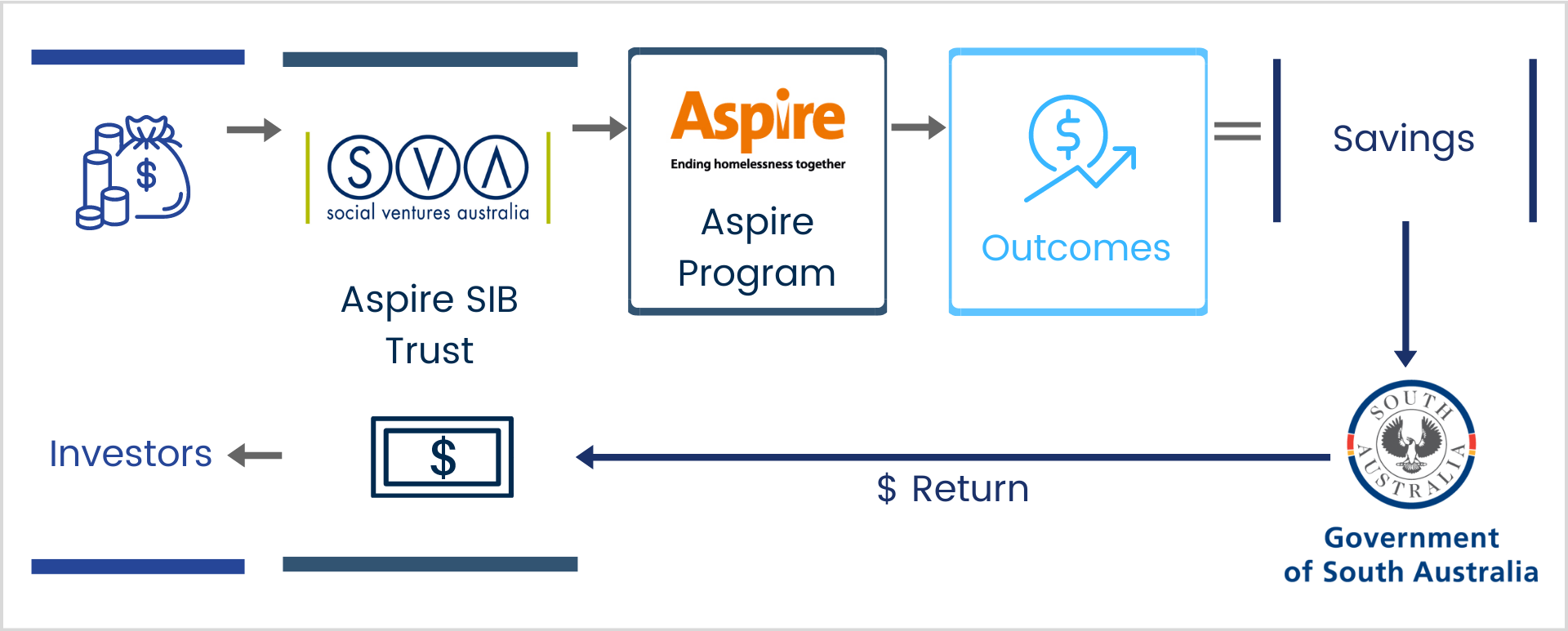

Impact focus: Homelessness, Employment

Description: The Aspire Social Impact Bond (Aspire SIB), Australia’s first homelessness focused SIB, raised private capital to fund the innovative Aspire Program, which is designed to make a difference to the lives of people experiencing homelessness in Adelaide. Hutt St Centre, a homeless services specialist, delivers the program. The program is also supported by housing partners including Common Ground Adelaide and Unity Housing. The $9 million Aspire SIB funds the program to work with up to 600 homeless individuals over 4 years. Structure: $9m bond

Financial Return: 8.5% target return over 7.75 years

Impact created: Funds the Aspire program for ~600 homeless persons in Adelaide for 4 years.

Impact focus: Mental Health, Community Services

Description: The Resolve Program is a recovery-orientated community support program in the Western NSW and Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health Districts. The Program offers a combination of a residential service for periodic crisis care, integrated psychosocial, medical and mental health support, and a warm line for after-hours peer support. Social Ventures Australia raised and manages the $7m Social Benefit Bond which supports the Resolve Program.

The Resolve SBB aims to improve the mental health and wellbeing of participants, while generating significant savings for the State through a reduction in participants’ utilisation of health and other services, by reducing the number of days spent in hospital. These savings will be shared with the mental health service provider, Flourish, to fund the delivery of the Resolve Program, and with investors to provide a financial return on their investment. Approximately 530 adults will be enrolled in the Resolve Program over five years.

Structure: $7m bond

Financial Return: Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 7.5% p.a. forecast over the 7.75 year note term

Impact created: Approximately 530 people enrolled in the Program can benefit from the service in the Western NSW and Nepean Blue Mountains LHDs over a five-year enrolment period:

-Program participants will collectively spend an estimated 13,300 days at Resolve centres over a seven-year service delivery period, diverting them from hospitalisation

-Target 25% reduction in the use of the health services compared to the Control Group

-$30 million in savings to the State through reduced consumption of health and other services

Impact focus: Employment services

Description: White Box Enterprises is a social enterprise intermediary focused on supporting and scaling job-focused social enterprises.

Structure: $3.8 million payment by outcomes trial in partnership with the Department of Social Services. Over 9 months, up to 170 people living with a disability will be employed by one of nine jobs-focused social enterprises selected to participate in the trial. The social enterprises will receive outcomes-based payments when participating employees maintain employment after 6, 12 and 18 months, with additional payments where a participant chooses to move on to work elsewhere.

Financial Return: Undisclosed

Impact created: Trial commenced September 2022 and is ongoing

Property

Impact focus: Sustainability

Description: IIG acquired the TAC building in Geelong in December 2014 for $95.8 million on a net passing yield of 7.5% per annum. It is an eight level A-Grade office building, built new for the TAC in 2008, who were the anchor tenant on a long lease. IIG sold the property in March 2018 for $115.25m on a passing yield of 6.83%.

Structure: Unlisted unit trust with $41.175 million equity from unit holders and $62.27 million loan facility from NAB.

Financial Return: 10% average cash yield. Overall IRR to unit holders of 14.9% (post fees).

Impact created:

Climate: IIG installed 39.9 kW of additional rooftop solar generation capacity abating over 47.8 tCO2e to June 2017. NABERS energy rating improved to 5.5 Stars from 5.0 Stars at acquisition.

Water: Connected toilet flushing to an existing 20,000 litre rainwater harvesting tank and installed an additional 5,000 litre tank, avoiding over 257,000 litres of municipal water from being wasted..

Place & Vitality: IIG created the ‘Impact Workshop’ in April 2017, a 40 desk co-working and innovation space for social purpose projects and organisations in the Geelong area. 20 desks were leased to TAC and Sprout Ventures manages the other 20 desks.

Impact focus: Environmental

Description: The IIG K1 Property Trust owns Kingsgate, a new Lendlease-developed office building, awarded the highest available NABERS energy rating: 6 stars. It is a 10 level commercial building at the gateway to the Kingsgate commercial precinct within the Brisbane Showgrounds urban regeneration precinct. It is tenanted to Lendlease, Medtronic and SMEC. IIG acquired the building for $141.2m in July 2015.

Structure: $63m of equity from unitholders, $78m of senior secured debt from NAB

Financial Return: 9.95% at end of FY17

Impact created: An Environmental Steering Group was established, with representatives from all major tenants. IIG works closely with tenants to monitor environmental performance and implement tuning and upgrade measures as identified, achieving a NABERS Energy Rating of 6 Stars. IIG allocates a portion of the management fees to the IIG Catalyst Fund, with the aim of directing funds into high impact opportunities.

Infrastructure

Impact focus: Renewable Energy

Description: Sydney Renewable Power Company (SRPC) provided funding for Australia's largest CBD Solar Array, on the roofs of the Sydney International Convention Centre Sydney (ICC Sydney).

The installation is 520kW, and all of the energy generated by the solar array is purchased and used by the ICC Sydney based on a 25-year power purchase agreement. A secondary revenue source is through marketing renewable energy offsets or certificates.

Structure: $1.55m loan in 2016 as initial bridge, $1.43m follow-up equity raising in 2017 to repay loan & fund working capital

Financial Return: ~4% (expected)

Impact created: Financed a 520kW solar photovoltaic installation on the rooftop of ICC Sydney, which will generate enough energy to power more than 100 houses. Following installation in mid-2016, first power was generated in December 2016, which enabled the first invoice to be issued in January 2017.

Impact focus: Renewable Energy, Indigenous community

Description: The 36-kilowatt solar power system was installed on the roof of a workshop and machinery shed in the Kurrawang Aboriginal Christian Community near Kalgoorlie as a joint initiative of the Not for Profit Alternative Technology Association (ATA) and the Kurrawang Community Board in 2016. Believed to be an Australian first, a $52,500 impact investment loan was provided by the McKinnon Family Foundation and the CAGES Foundation. The loan will be paid off by the community in 5 years, with savings on electricity bill exceeding monthly loan repayments.

Structure: $52,500 impact investment loan

Financial Return: ~8% over 6 years

Impact created: Expected to displace 20% of the community’s electricity use and to offset about 60 tonnes of carbon dioxide each year, equivalent to removing about 17 cars from the roads.

Fixed income

Impact focus: Climate Change, Renewable Energy

Description: CBA issued a 5-year Climate Bond in 2017. The proceeds fund eligible projects in renewable generation, energy efficient buildings and low carbon transport. Eligible projects which comply with the Climate Bond Standards and eligible for certification have been nominated for this climate bond. Eligible projects that meet the eligibility criteria of the Climate Bond Standards could be Nominated Projects including (but not limited to) solar, wind, hydro power, transport and energy efficient buildings.

Structure: $650m bond: $450m through a fixed income issue, $200m through a floating rate note. More details.

Financial Return: 92 basis points above relevant reference rate, 5 years

Impact created: Through supporting low carbon and climate resilient projects and assets, transition to a low carbon economy is enhanced

Impact focus: Sustainability, Environment

Description: Australian Catholic University (ACU) issued a $200 million sustainability bond in July 2017. The bond raised funds for a combination of social projects and green buildings that deliver positive social and environmental outcomes in line with the International Capital Markets Association's sustainability bond guidelines. ACU is the first university in the world to issue a Sustainability Bond. The debt is rated Aa2 (Stable) by Moody’s Investors Service and was arranged by National Australia Bank.

Structure: $200m Fixed Rate medium term note (MTN)

Financial Return: ~3.7%, paid semi-annually over 10 years

Impact created: Supporting the construction of green buildings as well as research and development programs with social impact.

Cash

Impact focus: Community

Description: Bank Australia is a customer owned responsible bank. Without shareholders, the bank’s profits are returned to its customers through better rates and fees. The funds are invested to create positive social and environmental change. It currently has 140,000 people and community sector organisations as customers.

Impact created: Profits are reinvested back into the bank to provide all customers with fairer feeds and better interest rates. They also invest 4% of the bank's after tax profit in a community investment program.

Fund managers and funds

In Australia, most products offered by intermediaries have been private equity, bonds, and property or loan funds. The table below highlights examples of Australian impact investment fund managers and some of the funds they have established.

Fund Manager | Example Funds | Description | |

| Impact Investment Group sources and develops investments that generate social and environmental value throughout the investment’s life, as well as delivering excellent financial returns for investors. | ||

| Impact Investment Fund is a specialised Impact Advisory and Fund Manager that aims to empower social innovators through connecting them to investors and offering a range of investments. | ||

| Indigenous Business Australia is a progressive, commercially focused organisation that promotes and encourages self-management, and sufficiency, as well as economic independence for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. | ||

| SEFA connects investor funding with social enterprises and mission led organisations. SEFA offers loan finance and capacity building support to enable community, environmental and indigenous enterprises to thrive and grow sustainably. It offers investors both social impacts and financial returns. | ||

| The Social Impact Investment Trust and the Diversified Impact Fund invest capital to help solve entrenched social problems. Investments include debt and equity into social enterprises, housing solutions and social impact bonds. |

Figure 2.3. Examples of Australian impact investment fund managers and associated funds.

2.3 Social Impact Bonds & Payment by Outcomes

Social Benefit Bonds or Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) are a type of financial instrument, and a form of social impact investment that have become increasingly popular - particularly in OECD countries - in recent years (5).

Combining in a single tool three core elements - entrepreneurship, innovation and investment - SIBs enable private investors to provide up-front funding to service providers to deliver improved social outcomes and address public concerns. If these outcomes are delivered, resulting government savings pay back the original investment plus a return (6).

As pressures on public budgets increase, a financing mechanism for social initiatives that promises to mitigate public sector risk, increase effectiveness, and pay for services now while requiring public contributions later, is likely to attract support (7). Since the first SIB was launched in 2010, there have been over 230 impact bonds globally in ~40 countries representing an investment of over $460 million in capital (8). Globally, SIBs are mobilising investments towards programs that are tackling complex social issues such as refugee employment support, loneliness among the elderly, rehousing and re-skilling homeless youth, and diabetes prevention.

Social Benefit Bonds provide a mechanism to share risk across investors, service providers and government. They offer their investors a blended return combining both financial and social outcomes (9).

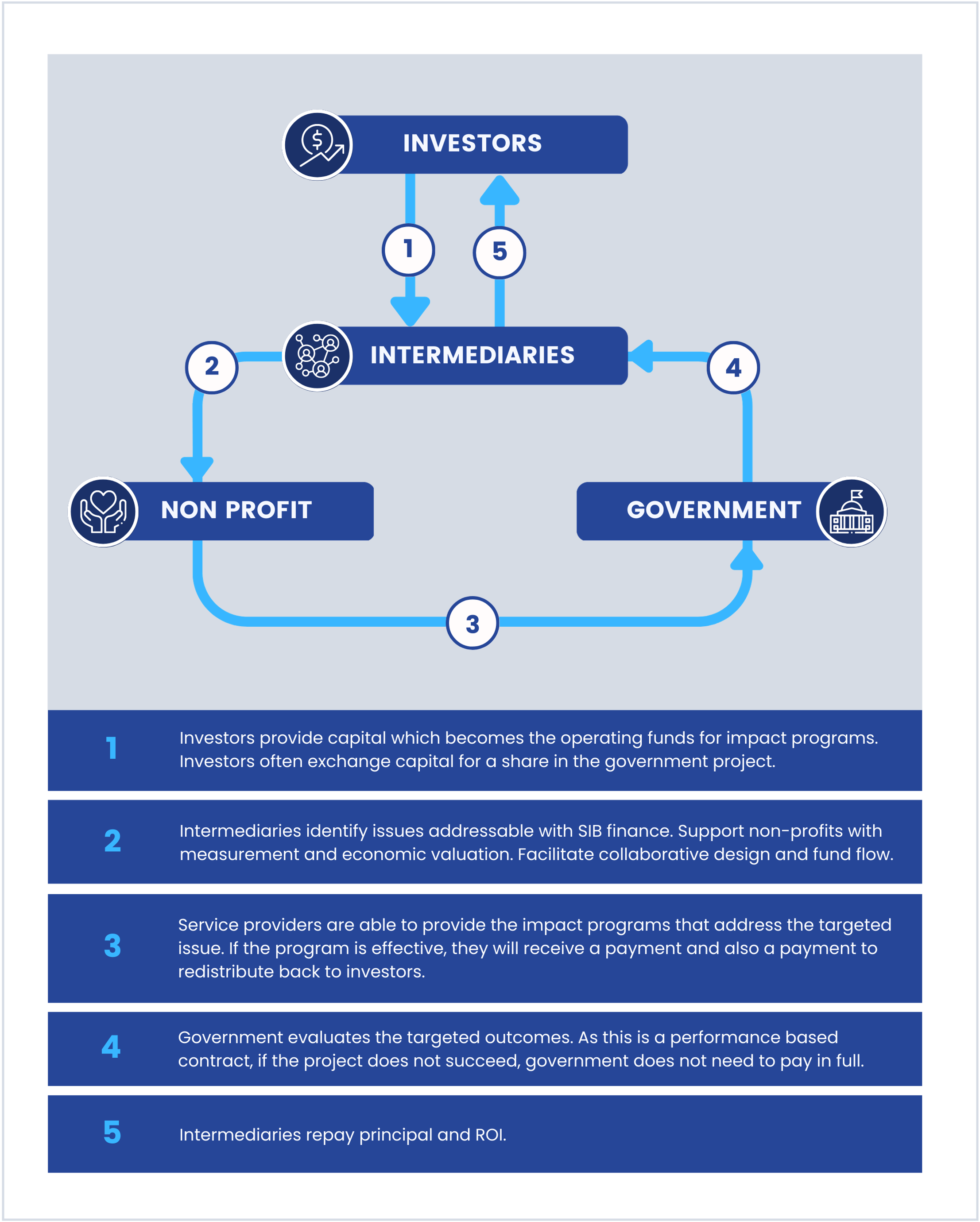

Figure 2.4 Overview of how a Social Impact Bond works.

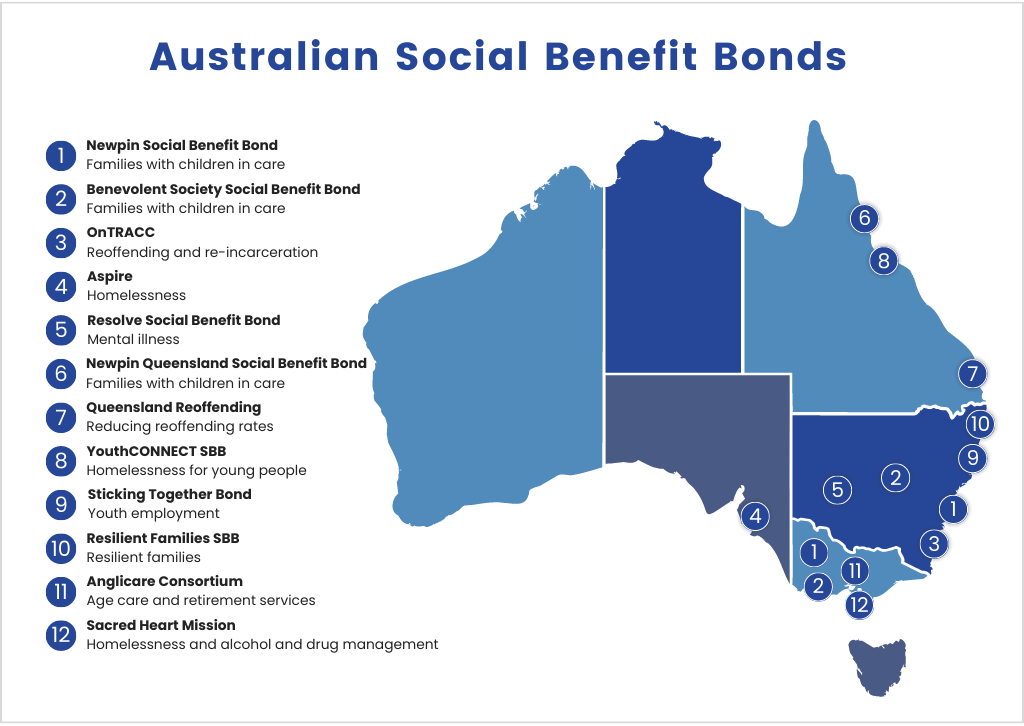

There are a number of Social Impact Bonds in the market in Australia, with New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, and Victoria all active in market (10):

Figure 2.5 Examples of Social Impact Bonds in Australia, based on Emma Tomkinson's SIBs in Australia (10)

Payment by Outcomes (PBO)

Social Ventures Australia (SVA) explain that Payment by Outcomes (PBO) are an outcomes-based contracting approach that governments use to commission a program for a clearly defined target cohort, with clearly defined outcomes. Typically, the performance of the program is measured relative to a baseline or counterfactual and payments are linked to the program’s performance as measured by the agreed outcome metrics.

This type of arrangement generates a financial risk for a service provider relative to traditional government grant funding – if performance targets are not achieved, then the service provider won’t be paid to cover its cost of delivering the program.

Spotlight on..

Aspire: a SIB focused on homelessness

Aspire Program

The Aspire Program is based on a housing first intervention model, and founded on the principle that people benefit more through first being given suitable housing followed by support in areas like health, education and employment. Participants will be provided stable accommodation, job readiness training, pathways to employment and life skills development. They will also have the long term support of a dedicated Case Manager to connect them with wider support services. (11)

The SIB

Aspire SIB is Australia’s first social impact bond focusing on homelessness and offers investors the opportunity to obtain a competitive financial return while making a lasting difference to the lives of people in Adelaide experiencing homelessness. The bond, underwritten by the South Australian Government, funds the Aspire Program, run by the Adelaide based homelessness services specialist Hutt St. Centre, in collaboration with community housing providers Common Ground Adelaide and Unity Housing Company.

The bond was oversubscribed and raised $9 million from private and philanthropic investors.

Key Features

- Investor returns are determined by Government payments to the Aspire SIB Trust, which are based on savings generated.

- Outcomes are determined by measuring health, justice and homelessness service utilisation relative to a historical baseline.

- A bond term of 7.75 years with a 2% p.a. fixed coupon over 4.75 years, then performance coupon based on the level of the Trust’s assets.

- In the event targets are met, investors can yield an estimated 8.5% per annum.

- Termination rights for poor performance to limit downside loss to approximately 50% of principal.

- Target scenario estimated return 8.5% p.a. (objective only).

Anticipated Impact

Approximately 600 adults who are experiencing homelessness are expected to be referred to the program over a four-year period, where each person will be provided support for up to three years.

An investor

The Aspire Bond presented a unique opportunity for the WC Rigby Trust, established to provide 'low cost housing for the poor'. Ben Clark of Australian Executor Trustees, which was appointed trustees of WC Rigby Trust in 1913, realised that Aspire presented an opportunity for the trust to invest capital to achieve a mission-aligned outcome. As Ben notes, before deciding to invest:

Our investment committee determined that critical to calculating the investment risk, was an understanding of the 'social' or program risk. In order to provide a qualified opinion, we needed to conduct additional due diligence on the capacity and capability of the charity partner delivering the Aspire program and it was not until we'd met with the CEO of Hutt St Centre and toured their premises, were we able to complete our due diligence and make a decision to invest.'

2.4. Green bonds

“Green bonds are innovative financial instruments where the proceeds are invested exclusively (either by specifying the use of the proceeds, direct project exposure, or securitisation) in green projects that generate climate or other environmental benefits...Their structure, risk and returns are otherwise identical to those of traditional bonds." UNDP, Financing Solutions for Sustainable Development (12)

The market for green bonds (also known as climate bonds) is one of the fastest growing in the world, estimated to be over USD 500 billion as of 2021 (13). The Australian green bond market is still relatively small, but current trends indicate it is growing rapidly as a diverse range of funds from institutional to ‘mum and dad’ investors subscribe for its bonds. Australia’s impact investing market is driven largely by the increase in green bonds. According to RIIA's Responsible Investment Benchmarking 2022 Report, green and social impact bonds represent 82% of the total impact investment market in Australia. Green, climate and social impact bonds were valued at $24.6 billion with the total impact investing market in Australia valued at approximately $30 billion (14).

In 2020 there were 10 major green bonds involving more than 100 Australian institutions (15). In 2018 the NSW Government raised $1.8 billion in green bonds, issued under the newly established Sustainability Bond Programme which will directed into projects that will deliver environmental and social benefits for NSW. The bonds have been issued by NSW Treasury Corporation (TCorp), the State’s financial markets provider and complement existing general purpose bonds already issued by TCorp. Other Australian organisations that are issuing green bonds include CBA, NAB, Westpac, Stockland, and Queensland Treasury Corporation. (16)

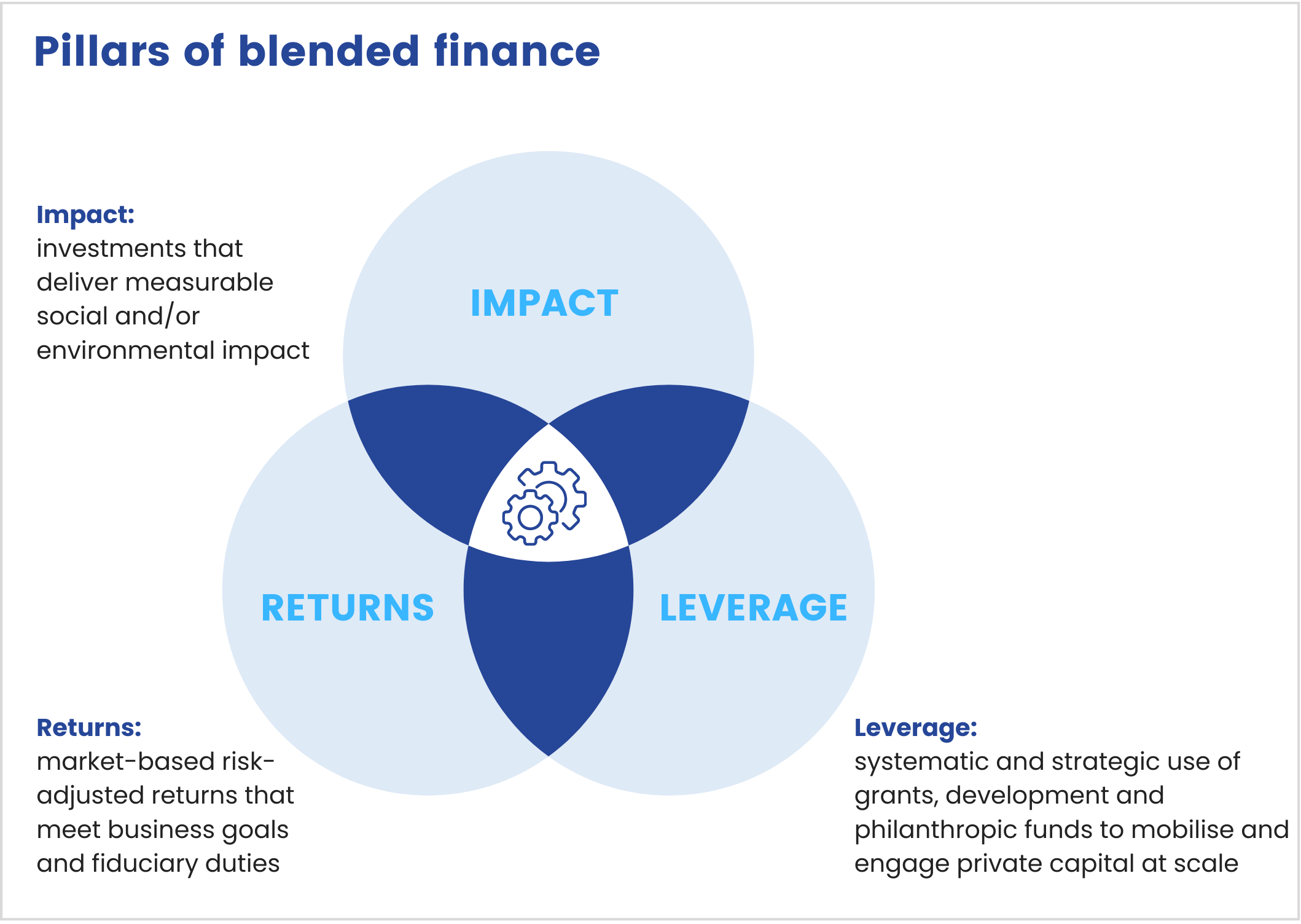

2.5 Blended finance and catalytic capital

The wide variety of types of capital available in social finance - and the complex set of risk and return calculations attendant on each type - offers opportunities for innovative structured deals and funds that do not exist outside of this [social impact] sector. It is suggested… that only such blends of capital may offer the critical support needed by socially entrepreneurial organisations if they are to tackle the ‘wicked problems’ currently confronting the world.” Alex Nicholls, Rob Parson and Jed Emerson, Social Finance (17)

Blended finance involves bringing together investors with different risk and return requirements to enable transactions that may struggle to attract pure commercial funding.

To leverage the significant capital needed to accomplish large-scale and sustainable impact, structures are needed that appeal to investors seeking full risk-adjusted returns. By deploying instruments such as grants, guarantees and impact-first capital to de-risk investments and lower the cost of capital, blended finance helps attract investors with a lower risk tolerance. Indeed, blended financed transactions do not require that all investors must have a social impact motivation.

Figure 2.6 Adapted from Blended Finance Vol 1: A primer for development finance and philanthropic funders, OECD & World Economic Forum, September 2015. (18)

Blended finance enables each public or philanthropic dollar to go further than it would on its own. For example, for every $1 received as a grant (eg. from a foundation), a deal may attract $5 from the private sector, given the improved risk-return profile attributed to the donor taking a first-loss position in a deal, or by providing a risk-sharing instrument like a guarantee. (19)

Globally, there is increasing interest in using blended finance to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Blended finance transactions have effectively mobilised over USD 51.2 billion towards the 17 SDGs. These ambitious targets require a new level of global cooperation to fund the required projects. As Lord Malloch-Brown, a former UK diplomat who chairs the Business and Sustainable Development Commission said (20):

“Action is needed end-to-end across the whole investment system to scale up the use of blended finance, if we are serious about closing the funding gap for the sustainable development goals.”

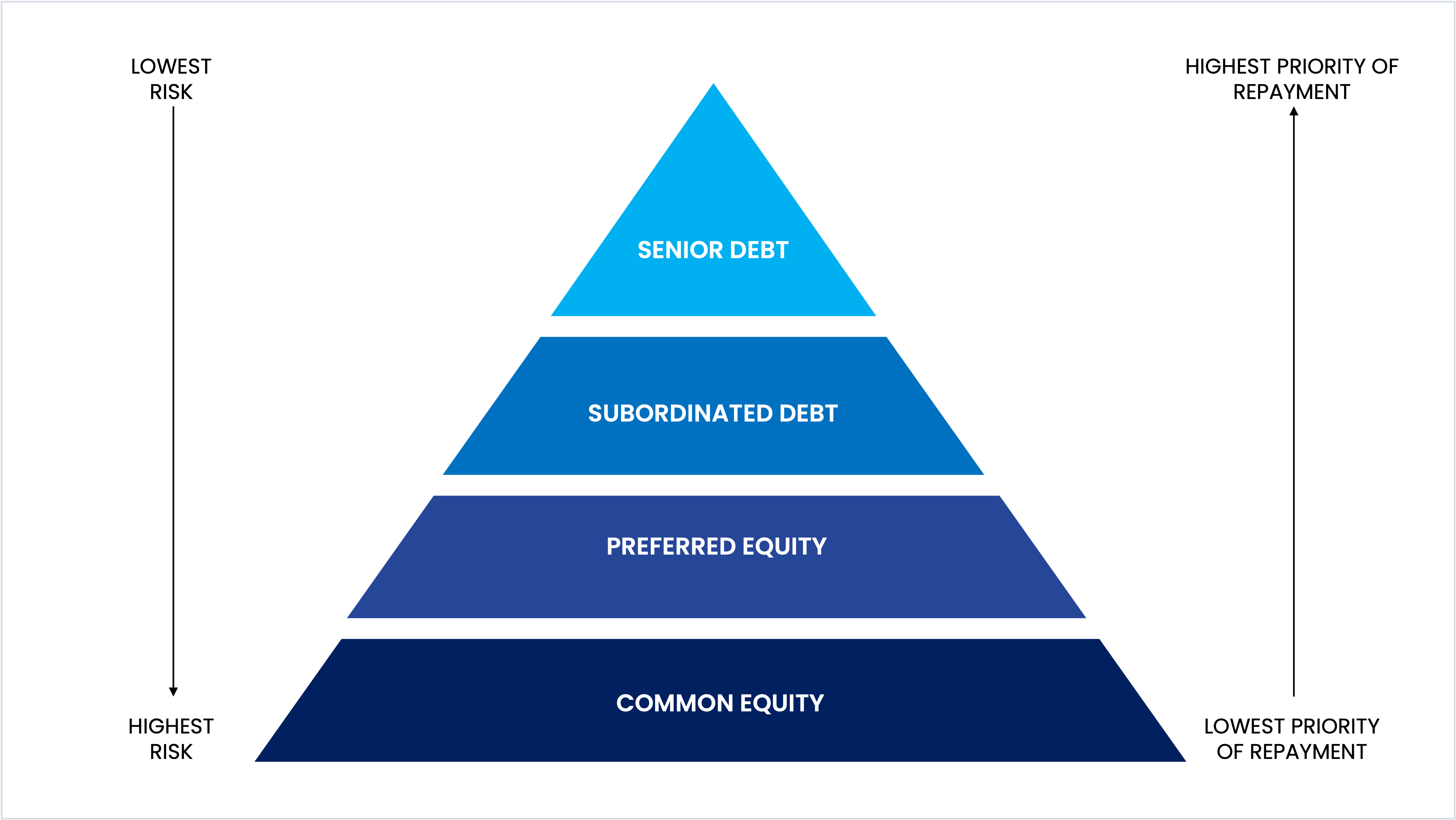

In blended finance arrangements, the philanthropic or impact-first capital may be considered as firs-loss capital. First loss capital refers to capital provided by an investor or grant-maker who agrees to bear first losses in an investment in order to catalyse the participation of co-investors that otherwise would not have entered the deal. There are a number of instruments that are commonly used to provide first-loss capital:

Instrument | Description |

Grants | A grant provided for the express purpose of covering a set amount of first-loss |

Guarantee | A guarantee to cover a set amount of first-loss* |

Subordinated Debt | The most junior debt position in a distribution waterfall with various levels of debt seniority (with no equity in the structure) |

Junior Equity | By taking the most junior equity position in the overall capital structure, the provider takes first losses (but perhaps also seeks risk-adjusted returns); this includes common equity in structures that include preferred equity classes. |

Figure 2.7 Adpated from the GIIN

*Note: if a Private Ancillary Fund (PAF) guarantees a financial institution’s loan to a Deductible Gift Recipient, the PAF can claim the discount between its income and the market interest rate as part of its distribution requirements (see Part 4, example 5).

Figure 2.8 highlights the differences in structure between regular finance and blended finance.

The term 'catalytic capital' refers to grants, guarantees, letters of credit, collateralisation, subordinated loans, concessionary or cornerstone investments that trigger additional capital not otherwise available. Catalytic capital often accepts lower returns to accommodate the economics of high-impact organisations that are profitable but not profit-maximising, whether due to an early stage of business development, tough markets, or a focus on impoverished populations.

Examples of how blended finance and catalytic capital have been used to bring high impact potential opportunities to life are explored in the Spotlights on the Vanguard Laundry Services, and the Journey to Social Inclusion deals below.

Spotlight on...

VANGUARD LAUNDRY SERVICES

The most exciting part about getting this deal up from the ground is seeing the impact it’s creating and its potential for replication. We are changing people’s lives with a blended finance model that really works, showcasing its massive potential.” Alex Oppes, SVA

Vanguard Laundry Services is a custom-built commercial laundry with a social outcome purpose of creating employment opportunities for Australians with mental illness. Involving over 50 parties, the Vanguard deal financed the building of the largest industry in Toowoomba, Queensland. The lead arrangers included Social Ventures Australia (SVA) and Vanguard’s founder, Luke Terry. Minter Ellison and King & Wood Mallesons provided pro bono legal assistance with Vanguard’s contracts and legal structure. This remarkable project demonstrates the challenges of leveraging social procurement and how to overcome them. (1)

Deal structure

The Vanguard Laundry Services deal was funded and developed through a complex blend of monetary and in-kind donations, government grants and fee waivers and debt financing, including:

- 1. The land for the laundry site was donated by Hallmark Property (alongside a project management fee waiver). The total value of the land and fee waiver was over $500,000.

- 2. $850,000 in monetary donations were committed by partners, including $600,000 from the Paul Ramsay Foundation.

- 3. Over $1,200,000 of debt was obtained through Westpac for the purposes of equipment financing. This debt was secured against the land donated by Hallmark Property.

- 4. $1,000,000 in Federal Government funding as well as a waiver of $150,000 in council fees by the Toowoomba Regional Council. The Federal Government funding was secured over the course of five instalments, with certain conditions precedent to funding (e.g. funding from other partners confirmed).

Outcomes

In the first year of operations, Vanguard Laundry Services reduced the number of participants reliant on Centrelink payments from 90.5% to 76.2%, and increased the median fortnightly income of participants by $392. This represented a 38.9% reduction in housing affordability stress.

After one year, all participants were able to record some employment experience (compared to 13.6% noting ‘no employment experience’ prior to commencement). Furthermore, 56.5% of employees recorded a history of ‘significant employment experience’ after a year of operations (compared to 31.8% 6 months prior to commencing). 78% of participants in the Vanguard Laundry Services program reported an improvement in health since commencing employment, with direct hospital savings estimated at just under $200,000.

The estimated five-year welfare savings to the government as a result of the program are estimated to be over $8.7m.

(1) https://www.socialventures.com.au/sva-quarterly/social-procurement-success-toowoomba/

Spotlight on...

JOURNEY TO SOCIAL INCLUSION

Traditional funding models for homelessness services don’t cut it for the client groups we’re targeting... J2SI's Social Impact Investment enabled us to access different types of capital, the types of capital that will allow us to provide support for sustainable change." Catherine Harris, Sacred Heart Mission

Sacred Heart Mission's (SHM) Journey to Social Inclusion (J2SI) is an innovative departure from traditional short-term, re-active homelessness interventions. It takes a housing-first approach and seeks to address homelessness and its associated challenges by providing relationship-based, long-term support for mental health and well-being issues, as well as resolving any drug and alcohol issues. J2SI also helps people to build skills and contribute to society through economic and social inclusion activity.

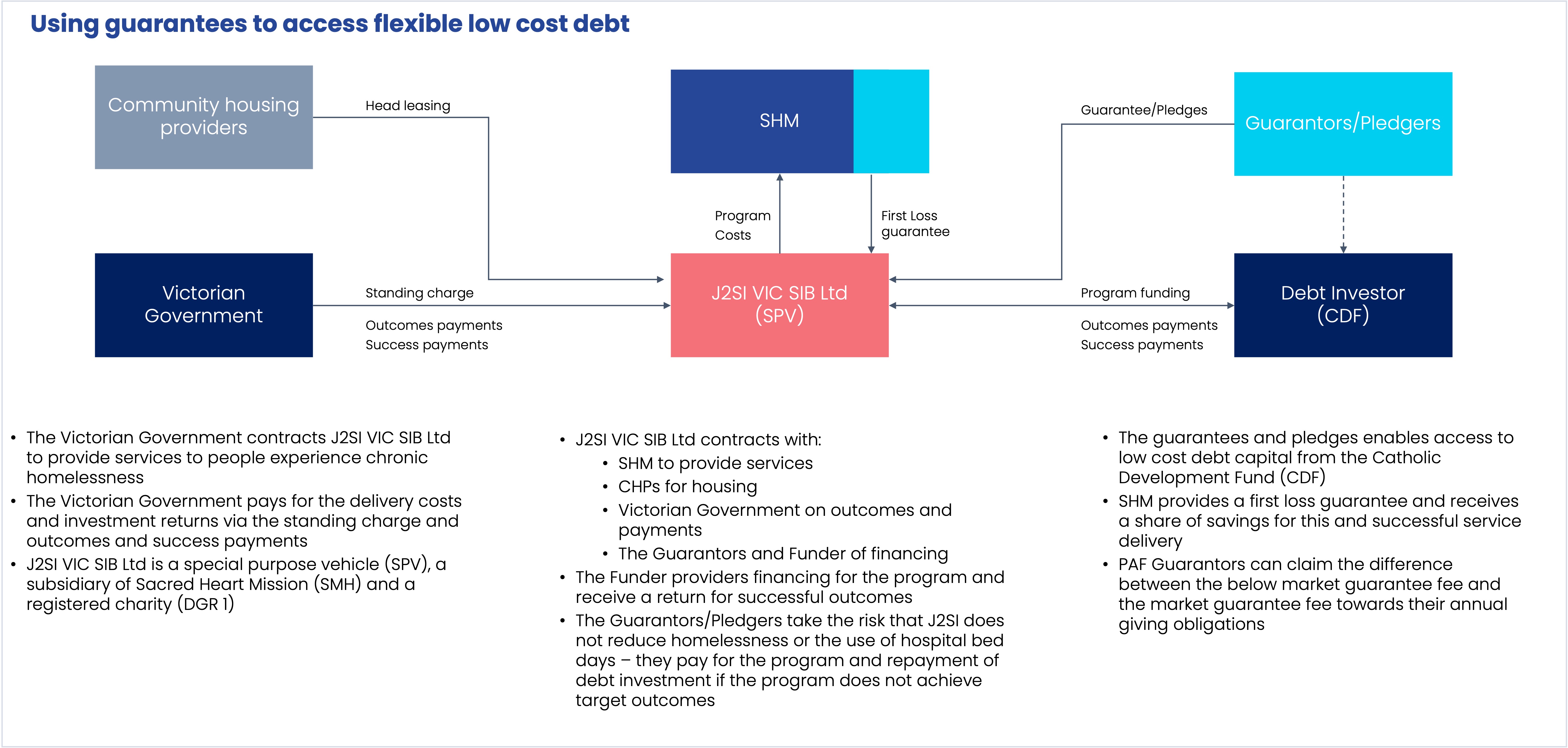

Structure of the deal

The J2SI Social Impact Investment (SII) is a unique partnership between government, the social services sector, investors and philanthropy, where the risk of achieving the outcomes for clients is shared between the parties, with the aim of achieving positive social change. The J2SI SII is the first social impact investment negotiated with the Victorian Government. The financing structure pays a return, based on agreed achieved social outcomes such as people staying housed and a lower use of healthcare services.

In contrast to a traditional Social Impact Bond, the SII accesses lower cost debt which is guaranteed by philanthropy if the outcomes for clients are lower than expected. In accordance with paragraphs 19 of the Private Ancillary Fund Guidelines 2009 and Public Ancillary Fund Guidelines 2009, the guarantee qualifies as a benefit and forms part of the annual distribution, as a below market rate guarantee fee is payable.

Social impact

Around 116,400 Australians are experiencing homelessness, and it is estimated between 23,400 and 38,300 of those people are adults trapped in a cycle of long-term, chronic homelessness with compounding challenges impacting their health, well-being, and employment. SHM, through J2SI, takes an evidence-based approach to homelessness, helping people with complexities put homelessness to bed and instead build a stable, independent life. J2SI SII will expand SHM’s J2SI program, to help 180 people in Melbourne break the cycle of homelessness over five years with three cohorts receiving three years of service. Service delivery commenced in August 2018. This will create lasting positive social change for communities and individuals.

Catalytic effect

In combining government financing, philanthropic guarantees, and low-cost debt, this transaction represents the first time low-cost debt with guarantees has been used to finance a SII in Australia, and demonstrates the strategic role of philanthropy in enabling social finance deals.

Catherine Harris, General Manager for Business Development at Sacred Heart Mission, says philanthropists were interested in the approach, however, a few were deterred by the concept of a “zero fee”, which was difficult for some investment committees even when the activity aligned with the foundation's mission. Harris commented:

Negotiating such a complex finance model was no easy feat. We've brought philanthropy and investors into the financial structure to share the risk. We did face challenges securing the partnerships, however. The challenge lay in getting people to understand the nature of the transaction and the benefits of long-term investing. The SII shows philanthropists can use their money, not as a handout, but also to enable programs such as J2SI to happen.”

Longer term, this transaction allows the J2SI model to be scaled and replicated under licence by social service organisations and state governments across Australia. SHM is developing a “J2SI product suite” and an Evaluation and Learning Centre to continue to refine the model so there is a real opportunity to expand J2SI around Australia to end chronic homelessness nationally using the new lower cost financing structure.

The NAB Foundation was one philanthropic party and provided a contingent pledge (similar to a guarantee) in the deal to ensure J2SI's access to low-cost debt capital. Lucy Doyle, Manager of the NAB Foundation commented that:

As a corporate foundation aligned with one of Australia’s major banks, we believe we have a responsibility to engage in financial innovation to help address complex societal challenges. Impact investing has the potential to unlock philanthropic capital, giving us an opportunity to move beyond traditional grant making to support the scaling and sustainability of proven impactful projects like J2SI.

PART 3

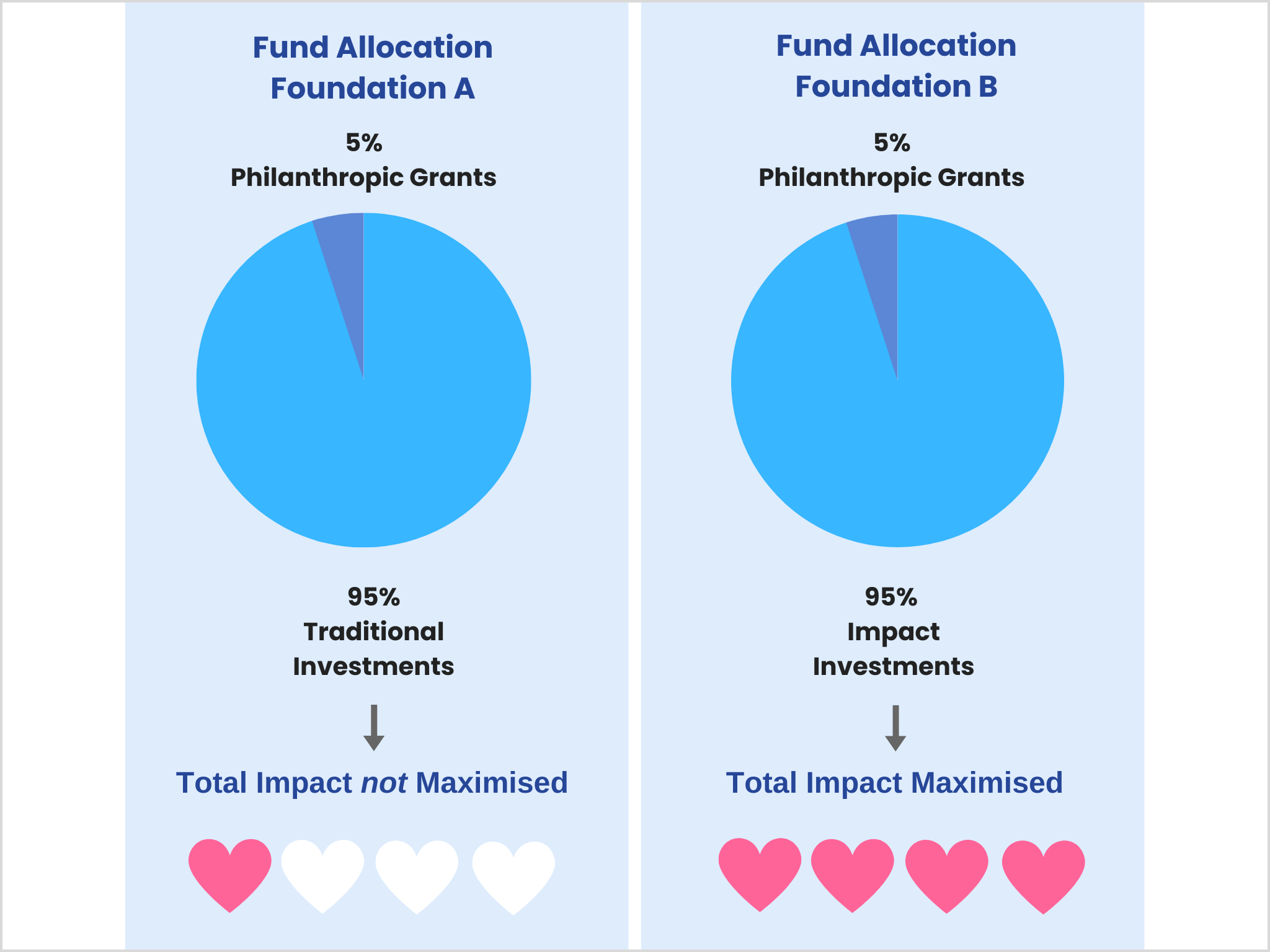

“If philanthropy’s last half-century was about optimising the five percent, its next half-century will be about beginning to harness the 95% as well, carefully and creatively.” Darren Walker, President, Ford Foundation

3.1 How to increase impact with impact investing

Where consistent with their Deeds, through deploying part or all of their corpus into impact investments, charitable trusts and foundations can engage with a greater set of solutions to address social and environmental challenges. They can amplify the positive impact they wish to have on on society, domestically and globally.

Charitable trusts and foundations are uniquely positioned to explore the opportunities presented by impact investing and to take the lead in shaping and developing the impact investing movement.

Firstly, they are experienced. Charitable trusts and foundations have engaged in mission or social investing long before the term ‘impact investing’ was first coined, and they have a deep understanding and fundamental commitment to social impact.

Secondly, charitable trusts and foundations can often provide more flexible, risk-tolerant, and patient capital than other types of investors.

Thirdly, impact investing can help charitable trusts and foundations to pursue their philanthropic mission more effectively by providing opportunities to direct more, and different, types of capital into delivering social and/or environmental good. Using the power of markets to address social and environmental challenges opens up new ways to complement and enhance the impact of grants. In particular, charitable trusts and foundations can deploy their capital in ways that catalyse and leverage capital from mainstream investors towards addressing social challenges; much larger amounts than they could mobilise on their own. (1)

And finally, impact investing can deliver social impact alongside financial returns—which can enable reinvestment of those funds in pursuit of even more social good. (2)

Figure 3.1 Experienced, adaptable, and mission driven

Funds under management represent the vast majority of a charitable trust or foundation’s assets but most commonly, these are applied primarily to achieve a financial return. Indeed, when invested in more traditional investments, these funds can even drive negative impacts, which undermine the purpose of the trust or foundation itself.

Impact investments allow for investment in opportunities from which all stakeholders can feel comfortable generating financial returns. They help ensure that your investments aren't working against the world you want to create.

To be clear, impact investing is not a replacement for philanthropy; some challenges simply cannot be tackled through market-based initiatives, and trustees are still required by law to abide by their distribution obligations. Instead, impact investing should be considered an additional tool in the toolkit of charitable trusts and foundations in maximising impact.

An impact investing strategy allows charitable trusts to align the values of their investment strategy with their grant making strategy. If they choose, foundations can intentionally seek out impact investments that directly advance the mission of the organisation. In this way, foundations have the opportunity to maximise their impact.

Figure 3.2 adapted from Charlton et al in the First Edition of the Field Guide (3)

3.2 What are Australian charitable trusts and foundations currently doing?

Impact Investing Australia’s (IIA) survey of Australian investors found that the majority of Australian charitable trusts and foundations are interested in making impact investments, with more than 40% actively investing. Whilst the survey is from 2016, the sentiment still holds that these organisations see opportunity to align more investment activities with their mission in the future, subject to suitable impact investments being available (4).

Similar to other markets around the world, Australian foundations are increasingly stepping into the impact investing space, exploring how to use more of their corpus for impact. Initiatives such as the UK's Social Impact Investors Group (SIIG) have inspired Australian foundations to come together and explore how they can collaborate, share experiences and work together to create better outcomes for the causes they support. Foundations such as Snow Foundation, McKinnon Family Foundation and Alberts Foundation are sharing their experience and expertise openly with others to encourage the sector to grow, with some of these organisations being recognised at the national Impact Investment Awards.

The role that Australian charitable trusts and foundations play is expected to further evolve as the sector develops and looks to other markets, such as the UK and the USA for inspiration. In the UK, the creation of Big Society Capital and Access Foundation, for example, have been instrumental in catalysing the growth of impact investing to support the UK's social enterprise sector. As Australia considers similar initiatives, Australian charitable trusts and foundations will have the opportunity to examine how they can best deploy their capital to create impact.

Spotlight on...

CAGES FOUNDATION: ALIGNING CAPITAL WITH PURPOSE

Since our inception in 2009, there has been a shift in the Australian impact investment sector. The market has grown extensively, there are more players in the field and more people making investments. Instead of just talking about it, investors are putting their money where their mouths are and deploying capital into the market. To get involved, you just have to be prepared to jump in somewhere and not get too caught up in the definition of what an impact investment is and how to define what you are doing.” Gemma Salteri, Executive Director, CAGES

Foundation

CAGES Foundation is a family-run foundation inspired by Paul and Sandra Salteri’s beliefs in giving back. Paul and Sandra established CAGES Foundation as a Private Ancillary Fund (PAF) in 2009. CAGES Foundation funds organisations working to improve the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged pre-natal to five years old. They direct their funding towards organisations that are locally owned and they have partnered with The Australian Literacy and Numeracy Foundation, Indi Kindi and several others.

Contributing to improving outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, CAGES Foundation’s Executive Director, Gemma Salteri notes that 'not all social issues that we are trying to solve can be solved by a loan. Apart from government, charitable trusts and foundations are one of the only entities that can effectively straddle both grants and investments. It is about balance and working with all of the assets that you have available to you.'

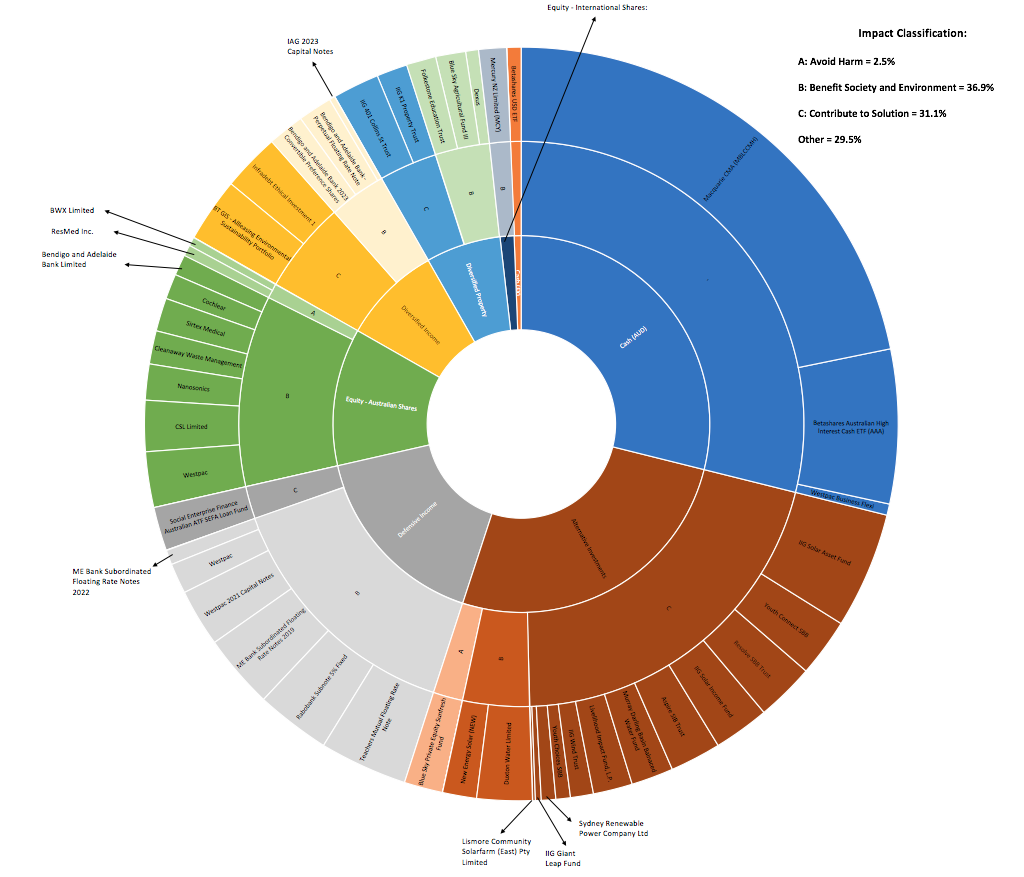

CAGES made its first impact investment in 2014 and currently has 40% of its portfolio in impact investing. They have investments across a variety of asset classes and consistently apply a strong ESG screen. CAGES actively pursues impact investment opportunities and as Salteri notes 'Hopefully the sector grows so that we will one day be able to achieve 100%.'

Their portfolio consists of both investments that generate a strong financial return as well as some higher risk capital deployed to principally create social impact, especially in the aligned area of stimulating Indigenous businesses. In the past, CAGES classified their impact investments as either Impact A or Impact B investments, where although both types of investments aimed to have a measurable social or environmental impact, the main intention of Impact A investments was to drive financial return, while Impact B investments had a bigger focus on social impact and did not have a market risk return profile. Rather than distinguishing between the two classifications, CAGES is now more focused on directing all their higher risk impact investments to supporting Indigenous businesses and impact investments that are more aligned to their mission.

CAGES aims to generate a financial return of 8% with its portfolio and being able to meet that target is important to them in being able to continue providing grants. Impact investing is very powerful but not all social issues can be resolved through investments alone. Having a balance between the two is very important and as Gemma says ‘There is no silver bullet, it has to be a mix.'

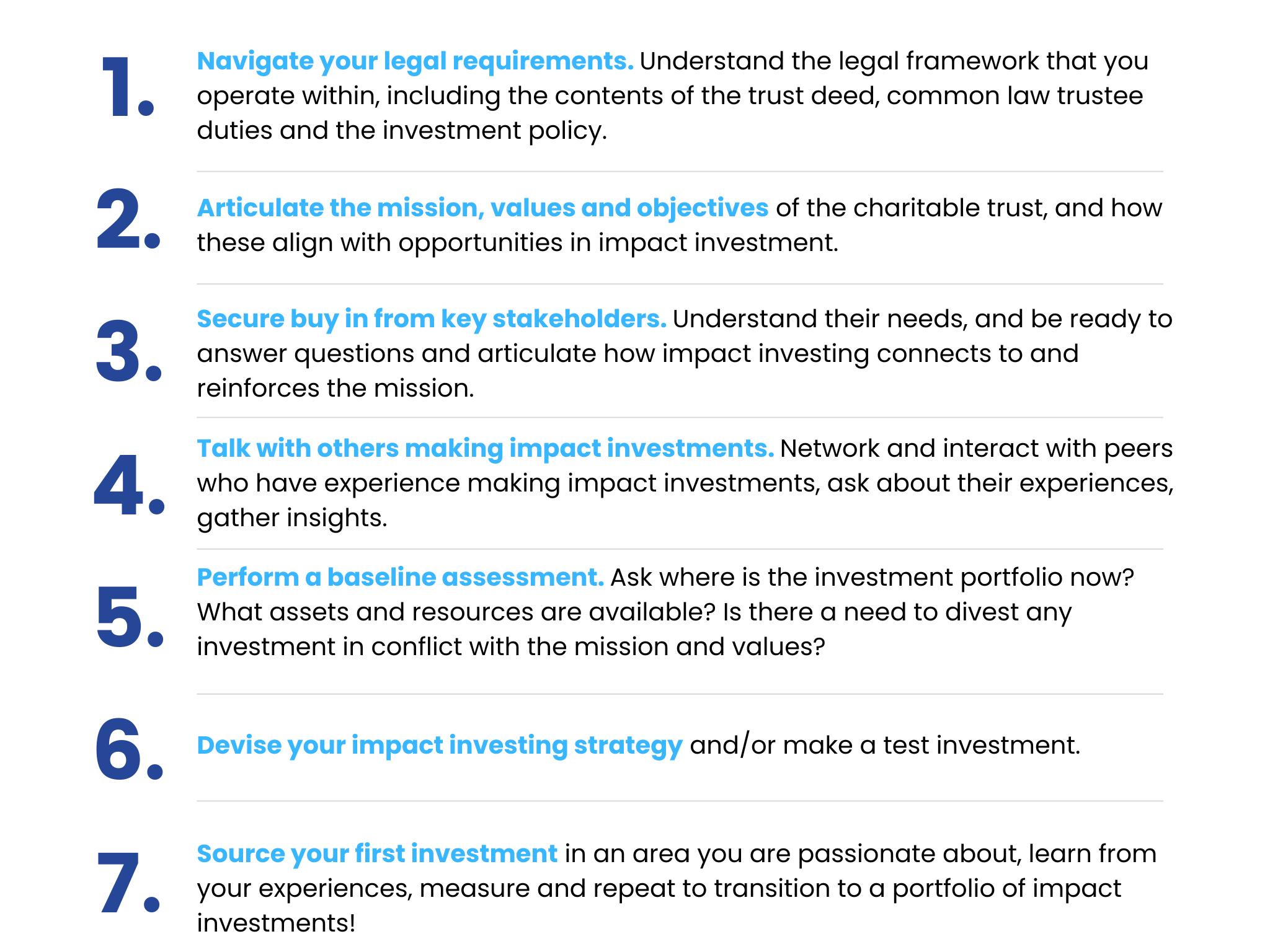

3.3 Identifying barriers & break down misconceptions & myths

Despite the intuitive rationale of impact investing and the fact that the approach has been well received internationally, Australian charitable trusts and foundations have been slow to adopt it. A relatively conservative culture around trustees’ duties and a lack of precedent have amplified trustees’ reluctance to experiment beyond the tried and true execution of their fiduciary responsibilities.

There are also a number of common myths and perceived challenges that have precluded charitable trusts and foundations from active participation in the impact investment market. Some of these common myths and challenges are addressed in the report Impact Investments: Perspectives for Australian Charitable Trusts and Foundations (6) and are explained in the table below.

Myth or Perceived Barrier | Response |

Uncertainty around investment duties of charitable trustees. Trustees of Australian charitable trusts and foundations may be uncertain about how to navigate their legal and investment duties and be wary that engaging in impact investments may be a breach of their fiduciary responsibilities (Cowan v Scargill [1985] Ch 270). | Whilst such caution is appropriate, the requirements imposed on trustees may be navigated in a way that permits the trustees to provide capital to enterprises and funds that pursue a social impact agenda. There is no difficulty with finance first impact investments, as they deliver a risk adjusted commercial return with the bonus of social impact. There may be challenges with impact first investments where there are discounted returns, depending on the structure. To pursue these, there needs to be explicit alignment with the Trust purpose as set out in the Deed. See also below information about discounted returns counting towards distribution requirements. |

Size of trust or foundation and resources needed is a barrier to entry. There may be a perception that only large foundations with significant staff resources can make impact investments. | Trusts and foundations large and small can and do make impact investments. Impact investments, like all investments, must suit your investment strategy. Larger foundations may be more able to dedicate resources to oversee impact investments, access different opportunities and do due diligence or more easily diversify their impact investments. But it is not the size of an organisation that inspires it to begin impact investing. Many of the leaders in impact investing are small to mid-sized and this hasn't stopped them from investing significant portions of their portfolios in impact investments. There are also a growing number of options available for foundations that want to invest through fund managers. |

Ambiguities about discounted returns counting towards minimum distribution requirements. Understanding when the difference between what the recipient pays and what would have otherwise been paid (i.e. the quantum of benefit) can be counted towards the minimum distribution. | Amendments introduced in 2016 to the PAF and PuAFs legislation addressed many of the ambiguities about what can be counted towards the minimum distribution requirements. The amendments added further examples to assist PAFs with calculating distributions where they have made social impact investments with eligible entities. See Part 4 for more details. |

Term confusion and understanding where impact investing sits in the portfolio. Differing definitions and philosophical approaches to impact investment have created confusion and uncertainty about where impact investing sits in the modern portfolio and how much to allocate to impact investments. | Whilst some argue that impact investment is an emerging asset class, the increasingly recognised view, endorsed by the Global Impact Investment Network (GIIN) and World Economic Forum (WEF) is that impact investment is a ‘lens’ that can be applied across mainstream asset classes. This is the definition that is adopted throughout this guide. Taking the integrated approach, Australian charitable trusts and foundations can apply an impact investment strategy to part or all of their investment portfolio, across all or selected asset classes. |

Uncertainty around achieving competitive financial returns as impact investments are higher risk. There is currently a perception in the market that impact investing necessitates both a high risk appetite as well as a financial trade-off. Despite sound financial returns in impact investments, there is a limited amount of public information that is published, hence creating scepticism. | Although there a relatively short track record of impact investing in Australia, most of the investments to date have achieved competitive financial returns. See Part 2 for investment examples. There is little evidence to support claims that impact investments have a higher financial risk than mainstream investments – it is evenly spread across the risk spectrum. However, there is an additional type of risk – impact risk. There is risk that the forecast impact may not materialise, or the investment may have unintended impacts. |

Limited access to expertise and lack of efficient investment infrastructure. Due to the relative immaturity of the Australian market, there are a limited number of impact investment experts and few resources that can help charitable trusts and foundations design and implement an impact investment strategy. The nature of impact investing requires market knowledge and expertise both on the financial side and on the social and environmental side. | As the market for impact investment in Australia matures, the pool of specialist consultants and intermediaries will grow, as will the impact investment infrastructure. This Guide seeks to consolidate the existing resources available in Australia as a step to improving the intermediation and infrastructure (see Part 6 for details of advisors in Australia).Further development of an investment infrastructure encompassing advisors, fund managers and product developers is required to accelerate participation in the market and drive down high transaction costs caused by fragmented supply and demand, complex deals and limited understanding of risk. |

Sourcing deals, limited absorptive capacity for capital and lack of track record. Lack of deal flow is often cited by Australian charitable trusts and foundations as a barrier to impact investing. There is a perception that most deals in Australia have been bespoke individual investment opportunities that present limited scale, liquidity, and diversification. | The number of deals and products available in the impact investing market in Australia is growing rapidly, as the infrastructure to support and develop that market. The Impact Investing Hub, launched in 2017, is a platform that connects investors with investees and impact investment opportunities. It also provides access to deals and key players in the impact investment market in Australia. Charitable trusts and foundations may also have the ability to partner with previous grantees to develop their own impact investment opportunities. |

Trust deed requires capital to be held in perpetuity and income to be distributed to one or more charitable purposes. Where the deed (or in wills that are the founding documents of the charitable trust) require the capital to be held in perpetuity, there is a constraint on all but finance first impact investments. | This barrier generally only applies to will trusts. |

Perceived barriers around managing risk and adapting mainstream investment decision frameworks. Investment decision frameworks for impact investments not only need to assess financial risk and return, but also the social risk (intended and unintended consequences) and return (the impact). | Adopting an integrated approach enables established investment decision-making frameworks, due diligence processes and portfolio construction models to be applied to an investment portfolio that includes impact investments. There are frameworks that provide a basis for developing and implementing an impact investment strategy across all or part of the portfolio. The GIIN and Rockfeller Philanthropy Advisors are examples to explore. Frameworks such as these help guide investors to establish portfolio parameters, define an investment strategy, asset allocation targets, determine an impact thesis, assess investment opportunities for risk, return and impact and manage financial and impact risk. |

Perceived barriers around classification of PAFs as sophisticated or professional investors. Currently, some PAFs are unclear whether they meet sophisticated or professional investor tests under the exemptions from the prospectus regime, despite very high net worth individuals or organisations (who themselves meet these tests) having established them. Many impact investing funds or social benefit bond offerings can only accept investors if they are sophisticated investors. | Under the current Corporations Act and accompanying regulations, a PAF would satisfy the sophisticated investor test if the PAF itself had net assets of at least $2.5 million, gross income of at least $500,000 for each of the last two financial years or paid at least $500,000 to accept an offer of securities. Alternatively, if the PAF itself did not meet the sophisticated investor test because of an insufficient level of assets or income, the PAF could satisfy the test if it was controlled by a sophisticated investor. The principal responsibility for ensuring this rests with the issuer, but there would be benefit in some regulatory guidance directed at PAFs which clarifies the operation of relevant provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). |